November 12, 2019

Diversity and the Power Balance of Language

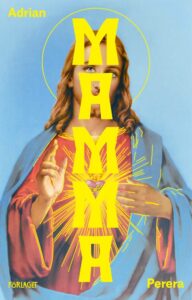

Sophie Ruthven looks at diversity through Adrian Perera’s book Mamma at our Edinburgh workshop.

Sophie Ruthven is an emerging literary translator of Swedish living in Innsbruck. She joined us for our translation workshop in Edinburgh.

A certain playfulness is required to sling possible Anglophone versions of kärring around a table with enthusiasm, and the group of often-solitary translators were certainly not left laughter- free at SELTA’s literary translation workshop in Edinburgh. Yet the duty of giving a text to a new linguistic audience is anything but light, and when the author has allowed their debut novel to be dissected (however lovingly) by a team of both experienced literary translators and those of us who are curious starters to the literary side of things, a lot of weight rests on picking the correct language. Even if the workshop is exploratory, even if the notion of completing the translation is purely hypothetical. Translators have a certain power which can be misused, and when the source text presents problems of power balance inherent in the use of different languages, we have to solve puzzles to the best of our ability.

Then again, can we always realistically carry out our task? This question arose during a workshop with the Finland-Swedish author Adrian Perera and his novel Mamma, one of whose characters is a multilingual mother living in Swedish-speaking Finland, viewed through the eyes of her son, Tony. We translators fell into what we do best: we zoomed in on the micro details of a text, sometimes losing sight of the text as a whole in the process. Though in the case of the extract from Mamma, we weren’t necessarily tying ourselves in knots over a curious adjective which didn’t sing in the English translation, rather the challenge of rendering a Swedish work in English, when the broken English of the protagonist Tony’s immigrant mother (spoken alongside Sinhala and Finnish), is, both in itself and its quality, a crucial part of the text, an indicator of both class and cultural difference, in a Swedish-speaking area of Finland. That’s a lot of layers of linguistic minority/majority interplay. There are footnotes which give clarity to grammatically problematic utterances, also serving to keep the narrative along the lines of Tony’s understanding. We considered adding some in to explain linguistic nuance, but then again, it would seem a shame to turn the book into a ‘Primer for Swedish Finland’, which would be both incorrect and potentially unreadable.

In his presentation of Mamma, Perera had floated the idea that no interpreter exists who doesn’t draw on something else with their interpretations, as all reality is inherently subjective. With the reader as the interpreter of the text after the translator has presented it to them in the reader’s own language: if the whole text is rendered in English, will the resultant invisibility of the English and foreign-ification of the Swedish parts disrupt the power-balance of the novel? Would an English reader judge the mother’s broken language in the same way as they would judge the doctor’s with whom she speaks’? Such a scene could be clearly read by a Finland Swede, but may become just a tangle of many Othernesses to an English language reader. The diversity which we wish to present to the new audience may end up simply invisible to that audience. Any good workshop often throws up more questions than answers, though it’s curious to be stumped over whether something can be translated at all.