November 11, 2022

SELTA at 40: Kate Lambert

Kate Lambert joined SELTA in about 2014 but has been working full-time as a freelance translator since 1997.

When did you join SELTA?

About 2014 or so? In 2013 I went to the BCLT summer school to see whether I was any good at translating literature with people who translated literature. Everyone was welcoming and some of the other people there were SELTA members and they said I should join as an associate. It was the first indication I had that the world of literary translation wasn’t an elite club.

What kinds of things was SELTA doing when you joined?

The first event I attended was the children’s literature translation workshop in autumn 2014. I think the events where we get to compare translations with each other (anonymously) and talk about choices made in detail are really valuable when we tend to be working in isolation the rest of the time.

When did you join the committee and what is your role?

Six years ago. I think it was either the first or second meeting I attended. Ian was moving to be treasurer and that left a vacancy for the web manager post. I made the mistake of saying “what content management system is it based on and where is it hosted?” and the meeting promptly concluded that I knew more about websites than anyone else there and should take it over. For the first couple of years I couldn’t do very much as the old website was rather on its last legs but then we had a new one developed and I’ve been involved in getting that functioning, getting everyone using it and updating it. Doing this 40th anniversary project has been great fun and I hope the pieces by members give a picture of the wide variety of things that members translate and the way careers and the industry have changed over SELTA’s history.

Tell us about your career – where did you learn Swedish, how did you become a translator?

I went to UEA to study History with ancillary Swedish in 1986. The course was intended to give historians enough Swedish to read source documents in the original language (which was probably a bit optimistic) but everyone else learning Swedish was doing it for their degree and halfway through the first year I switched to joint honours making it a 4-year course with the second year abroad at a folk high school. In my final year we had to do a dissertation and I lazily decided that doing a translation would be much less effort than doing a history project. I translated extracts from Torsten Ehrenmark’s Mina osvenska år, funny stories about being a Swede living in the UK, and I absolutely loved it. I knew this was what I wanted to do forever. I just didn’t know how you became a translator or if it was even a job really and no-one at UEA in 1989 mentioned it as a possible career. So I went to teach English in a Finnish hydroelectric power company on the Arctic Circle instead.

I taught English in Finland for four years in the end, one in Rovaniemi and three in Mikkeli, and although it was the early 1990s, in the days before the internet, my experience was very similar to Harry Watson’s in Sweden 20 years earlier. My mother used to send me cassette tapes of The Archers and I used them for listening comprehension because I couldn’t get English materials otherwise. I also had to write an entertaining weekly column about Finland “Through Foreign Eyes” in the local paper. In the summers (they didn’t pay me for the summers) I came back to my parents’ farm and went to the library to look at careers guides to find out how you became a translator. I found that there was a Swedish translation MA at the University of Surrey and that I couldn’t get funding for it so I carried on teaching English to Finns until I had saved enough money to pay my fees and my living expenses.

I taught English in Finland for four years in the end, one in Rovaniemi and three in Mikkeli, and although it was the early 1990s, in the days before the internet, my experience was very similar to Harry Watson’s in Sweden 20 years earlier. My mother used to send me cassette tapes of The Archers and I used them for listening comprehension because I couldn’t get English materials otherwise. I also had to write an entertaining weekly column about Finland “Through Foreign Eyes” in the local paper. In the summers (they didn’t pay me for the summers) I came back to my parents’ farm and went to the library to look at careers guides to find out how you became a translator. I found that there was a Swedish translation MA at the University of Surrey and that I couldn’t get funding for it so I carried on teaching English to Finns until I had saved enough money to pay my fees and my living expenses.

The Surrey MA was in economic, technical and legal translation from Swedish and Norwegian and was an excellent practical training course that convinced me I shouldn’t go anywhere near translating accounts or technical translation ever again. After that I taught on the same MA, teaching the legal module, had an in-house job for a year and then I went freelance in 1997. In the 2000s I spent 8 years working in partnership with a colleague and I miss having someone around to talk about work with. It also enabled me to give myself maternity leave three times without my business disappearing.

What are some of your most interesting translation projects?

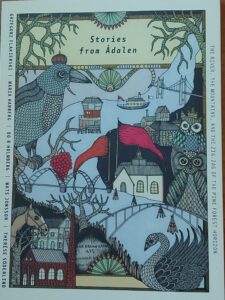

Ebba Witt-Brattström’s Love/War, a divorce novel told entirely in dialogue with loads of quotes to look up. Others that stand out are the biography of Albert Bonnier, which involved a lot of history research and a Finnish YA novel about Basque whalers murdered in Iceland in 1615 which involved a lot of history research. I also enjoy the work I’ve done for museums, including an exhibition about sunken ships that included lost letters from Catherine the Great to Voltaire, diagrams of historic Dutch sailing vessels and diving logs, and auction catalogues filled with Swedish art and design. I enjoy getting the right voice for each varied project. Like being an actor but for introverts. And I have realised that although I veered away from my history degree, I still really like historical research.

Ebba Witt-Brattström’s Love/War, a divorce novel told entirely in dialogue with loads of quotes to look up. Others that stand out are the biography of Albert Bonnier, which involved a lot of history research and a Finnish YA novel about Basque whalers murdered in Iceland in 1615 which involved a lot of history research. I also enjoy the work I’ve done for museums, including an exhibition about sunken ships that included lost letters from Catherine the Great to Voltaire, diagrams of historic Dutch sailing vessels and diving logs, and auction catalogues filled with Swedish art and design. I enjoy getting the right voice for each varied project. Like being an actor but for introverts. And I have realised that although I veered away from my history degree, I still really like historical research.

How is the world of translation today different to when you started out?

I feel like I bridged the gap between the old world and the new! When I first went freelance I had one client who wanted my translation printed and sent on paper. The MA had taught us word processing and I was thrown by not being able to make any last-minute changes before sending the file because I would have to print the whole thing out again and miss the post. That client did retire shortly afterwards. But at the start most of my work came in as faxes and you put the fax sheets in a document holder and typed the translation in on screen. I remember a whole series of market research forms from Finnish farmers about their tractors that came in in the post bearing ominous stains, having been filled in in pencil in block capitals, looking as if the respondents had been leaning on their tractors at the time. (I know I said no technical but I have a father and a sister to ask expert things about tractors and I feel if Finnish farmers are cross about a part of their tractor that keeps falling off or think the dealer in Oulu is fantastic, the parent company should know about it in their own words).

When I started out, the translation was either faxed back or some modern translation agencies had modems which you dialled into via your computer to deliver the file electronically. I still really appreciate no longer having to spend hours checking I have typed in numbers and addresses correctly. When I worked in-house, my boss had the computer with the modem and The Internet and if I wanted to look up anything online, I had to write it down and then use his computer to go online while he was at lunch. For EU documents and anything scientific, I had to walk across town to the university library. It’s not that long ago but it feels like a different world.

Did your career trajectory change? Is it different now compared with what you expected at the start?

Originally (see above) I wanted to be a literary translator. In the 1990s I met a friend who worked in publishing and asked how you got to translate books. The answer was a) “Find a rich husband” and b) “Wait for Joan Tate to die”. This sounded a) depressing and b) callous so I kept going on my non-literary translation career. I definitely got the impression in the 1990s that literary translation was a closed shop that I had no hope of getting into. I concentrated on making my translation work as creative as possible, which included non-fiction books on tourism and architecture and marketing and advertising alongside the paper mills and EU and government reports. I like reports on interesting things. Although I have now translated published fiction, I like the mix of translation career I’ve got and the fact that it is never dull. And my publishing friend had a point in that it would have been impossible to survive as the main/single family breadwinner on literary translation alone. I earn a decent living from the mix I’ve got.

Originally (see above) I wanted to be a literary translator. In the 1990s I met a friend who worked in publishing and asked how you got to translate books. The answer was a) “Find a rich husband” and b) “Wait for Joan Tate to die”. This sounded a) depressing and b) callous so I kept going on my non-literary translation career. I definitely got the impression in the 1990s that literary translation was a closed shop that I had no hope of getting into. I concentrated on making my translation work as creative as possible, which included non-fiction books on tourism and architecture and marketing and advertising alongside the paper mills and EU and government reports. I like reports on interesting things. Although I have now translated published fiction, I like the mix of translation career I’ve got and the fact that it is never dull. And my publishing friend had a point in that it would have been impossible to survive as the main/single family breadwinner on literary translation alone. I earn a decent living from the mix I’ve got.

One new and unexpected turn that things have taken in the last couple of years is a sudden demand for English translations of Nordic knitting books, where I seem to be quite niche in knowing both Finnish and how to knit socks.

How has being a SELTA member helped in your career (if it has!)

I have been lucky enough to be mentored by both Ruth Urbom (for Finnish) and Sarah Death (for Swedish). Although these mentorships weren’t run by SELTA itself at the time, both my mentors are SELTA members and I benefitted hugely from their support, encouragement and advice.

Otherwise, it does feel like being part of a community. Of course we are in competition with each other but we also share information, support each other and pass on work that might not suit us but might be perfect for someone else.

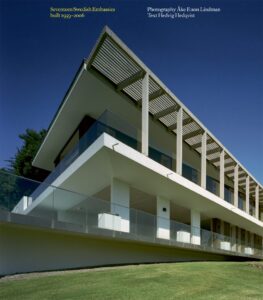

Photo: cover of 15 Swedish embassies translated jointly with Stuart Tudball.