October 24, 2022

SELTA at 40: Eivor Martinus

Eivor Martinus is a founder member of SELTA and served as its Chair for many years. In this interview, she looks back at SELTA’s early years and at her career as a writer and translator.

When did you join SELTA?

I have been a member of SELTA since 1982.

If you are a founder member, how did the decision to form SELTA come about? What other SELTA names do you remember from that era?

Tom Geddes was the driving force then and without him SELTA would never have come into being or flourished later on. Although he is a very unassuming person he was deeply involved in every aspect of the association. He avoided taking the Chair but he was the actual ‘leader’ for a long time. It could occasionally mean the exclusion of other members but mainly because no one else offered their services – for several years. We had a committee but most of the members were rather passive.

During my fifteen years as Chair I made sure that the committee consisted of people who were allotted a special task. That made it easier to resign and hand over to the next person, in my case, the very competent Ruth Urbom.

Apart from Tom Geddes other colourful early members were Joan Tate, Patricia Crampton, Ann Henning and Laurie Thompson. Ann Henning and David McDuff also joined us during the first period, but I am not sure exactly when.

As Literary Translators we felt there was a lack of communication between us and the literary establishment. We were all working in isolation. The Cultural Attache became an early ally of SELTA and helped us with meeting room, subsidies and the handling of the Bernard Shaw Prize.

Joan Tate insisted that the Association should be about Literary Translators rather than Technical or Academic Translators. She thought there was a great divide between those who were employed by universities and people like her who struggled on a freelance basis. There were exceptions to that. Laurie Thompson, for instance, was a lecturer at Lampeter University and as Editor of Swedish Book Review he could use the facilities there to publish our magazine. There was no Internet in the early eighties so everything took so much longer than today.

Tell us about your career – where did you learn Swedish, how did you become a translator? What are some of your most interesting translation projects?

From an early age I had one foot in each country and my degree in English (specialising in Literature before 1800) and Litteraturvetenskap at Gothenburg University, which included World Literature, turned out a very good choice for my future career. I was broadly educated in Sweden but moved to this country before I was twenty, finishing my degree here.

From an early age I had one foot in each country and my degree in English (specialising in Literature before 1800) and Litteraturvetenskap at Gothenburg University, which included World Literature, turned out a very good choice for my future career. I was broadly educated in Sweden but moved to this country before I was twenty, finishing my degree here.

I started out as a novelist, published one adult novel and four youth fiction novels before starting to translate. Since I was involved in the theatre and worked on fifteen productions with my late husband who was a theatre director it was natural for me to carry on translating and adapting drama.

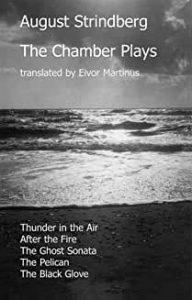

Altogether I have translated fifteen Strindberg plays who have all been published and twelve of them have been performed either in England or the US. In the nineties I was commissioned to translate a number of Swedish classics for the BBC Drama Department: Hjalmar Söderberg’s Gertrud, Hjalmar Bergman’s Markurell i Wadköping, Pär Lagerkvist’s Barabbas and Ingmar Bergmans En Själslig Angelägenhet.

In Sweden I worked on English classics in my Swedish translations for various theatres: The Shoemaker’s Holiday by Thomas Dekker, The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists by Stephen Lowe and Mad Forest by Carol Churchill.

In Sweden I worked on English classics in my Swedish translations for various theatres: The Shoemaker’s Holiday by Thomas Dekker, The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists by Stephen Lowe and Mad Forest by Carol Churchill.

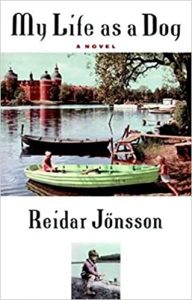

In the eighties I also translated two Swedish novels: The Mysterious Barricades by Bengt Söderberg and My Life as a Dog by Reidar Jönsson. Bengt and I corresponded regularly during my work on his translation and when I got to a passage where Bengt had translated something from Racine I asked him in exasperation, what do you want me to do with this? He had been using his own translation of Racine but what should I do? I could not very well use an existing English translation. No, since I used my own translation, said Bengt, I suggest you simply cut it in your English translation. That led to one critic accusing me of neglect or, worse still, ignorance. But every move was endorsed by Bengt so I felt rather disappointed.

After my decade of drama translations for the BBC, I turned to biography and published two books about Strindberg and his women, a biography on Queen Filippa of Sweden-Denmark and a few more personal books, including one about Saint Birgitta and her daughter Katarina.

How has being a SELTA member helped in your career (if it has!)

I can’t honestly say that being a member of SELTA has helped me in my career. It is quite a lonely road but it has been fun meeting other wordmongers at regular intervals.