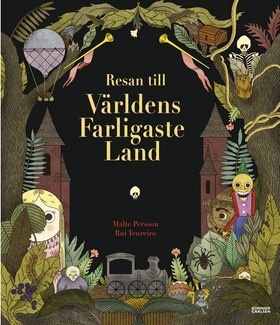

Author and poet Malte Persson joined four other Swedish writers who came to London in November to participate in a day of practical literary translation workshops with SELTA members. Since his literary debut in 2002 with the novel Livet på den här planeten (‘Life on This Planet’), Malte Persson’s output has encompassed fiction, poetry, literary criticism and children’s literature. He has received a number of awards for his work, including the 2012 Tegnér Prize, and was nominated for the prestigious August Prize in 2008 for his novel Edelcrantz förbindelser (‘Edelcrantz’s Relations’). In this guest post, Malte reflects on workshop participants’ various translations of an extract from his 2012 children’s book, Resan till världens farligaste land (‘Journey to the World’s Most Dangerous Land’). The English translation here is by Nichola Smalley.

We Swedes are so used to reading and hearing English that you can start to convince yourself you’re completely fluent in it. That’s wrong, of course. I wish I could translate myself, but every time I try, I have the distinct feeling that my English, even if it should happen to be grammatically correct, doesn’t really sound like normal English. And what’s worse: I have no clue whether it sounds abnormal in a good, intentional way (which even my Swedish does sometimes) or if it just sounds weird.

That’s why we need translators – these often all-too-anonymous wordsmiths at the literary anvils of our ungrateful book market. In any case, discussing and trying to solve translation problems is one of the funnest things I can think of, and it was a privilege to get to take part in SELTA’s seminar on the translation of Swedish children’s and YA literature in London on 7 November this year. The highlight for me was of course the workshop in which I and a group of translators discussed six different versions of an excerpt from Resan til världens farligaste land, a picture book by me and illustrator Rui Tenreiro. Even the title is complicated: ‘The Journey to the World’s Most Dangerous Land’, ‘Journey to the World’s Most Perilous Land’, ‘Journey to the Scariest Land in the World’, or perhaps ‘A Journey to the World’s Most Fearsome Land’… And it just keeps on getting worse.

The book’s fantasy world is full of dangers. After crossing a dangerous sea, you come to a spooky shore, and beyond the shore you find first a forest full of trolls and kidnapped children, and then a dangerous bog, which we can take as an example of the difficulties a translator also encounters during the journey. In Swedish, it says: “I skogen ligger världens värsta träsk / som bubbler brunt som kolaläsk.” And here are the various English translations, which are remarkable not least for the fact that they are so varied:

You’ll find a bog, in all the world the worst,

where bubbles brown as toffee cola burst.

The forest’s swamp is truly deadly,

Bubbling up like a can of Pepsi.

In the forest, the world’s most hideous bog

bubbles brown and dank under odious fog.

In the forest lies the world’s worst blistering bog:

Cola-dark its bubbles rise as from a drowning dog.

Deep in the forest the world’s worst swamp can be found,

like cola pop its brown mud fizzes and bubbles around.

The world’s worst swamp you’ll find there too –

It bubbles up like thick brown stew.

In Swedish, the ‘träsk’ (bog/marsh) bubbles brown like a fizzy drink, but which fizzy drink? There’s a double meaning in the ‘kolaläsk’ – should you be thinking about something in the Coca-Cola genre (‘cola’ in Swedish) or a fizzy drink that tastes like toffee (‘kola’ in Swedish)? This double meaning can’t be reproduced in English. The translators have chosen different alternatives here, or even exchanged the image for another. Personally, I like the creative half-rhyme of ‘Pepsi’ and the addition of ‘like a drowning dog’, which isn’t in the original, but retains its drastic spirit. Exchanging the untranslatable fizzy drink for a ‘thick brown stew’ is totally fine too.

Then we have rhyme and metre – the original is somewhat irregular; some translators have made it even more irregular, others have made it more regular in English. As a fan of Alexander Pope, I wouldn’t have had anything against being translated into ‘heroic couplets’, as in ‘You’ll find a bog…’ But opinions were strongly divided as to which was preferable. It’s safe to say, though, that you can only succeed with a translation like this if you’re daring enough to take pretty big liberties with the original text.

As an author, one can dream of being translated by the joint labours of a great committee of translators, but alas, that’s hardly realistic… and in any case, finding a competent translator is less difficult than finding a publisher prepared to take the risk of publishing a translated book.

Between the presentations and workshops, there was time during the day for informal conversations and a huge amount of sandwiches and cakes. I hope the participating translators found it as rewarding as I did.

*****

Per Gustavsson is a Swedish author and illustrator who travelled to London in November 2014 to take part in SELTA’s event on children’s and young adult (YA) literature. In addition to being a member of the Swedish Academy for Children’s Books, Per has won a number of awards for his work. His most recent prize is the 2014 Elsa Beskow plaque for the year’s best Swedish illustrated children’s book, which he received for Skuggsidan (‘Shadowside’, 2013). In this guest post, Per shares his reflections on the day of workshops and discussions. The English translation here is by Ruth Urbom.

The one thing I miss from my time at school (my education as an illustrator/designer) is the group crits where everybody had to present their own solutions to a given task. I was always amazed at all the solutions I was never an ywhere close to. They might not always have been better. But just the fact that they were new ways of looking at the problem was inspiring.

ywhere close to. They might not always have been better. But just the fact that they were new ways of looking at the problem was inspiring.

A couple of years ago, a fellow illustrator (Helena Willis) and I worked on a project to write and illustrate a book together. We wrote a story and figured out the pagination, and then we each went off to our own studios to sketch out the book. It was incredibly exciting to see how we had dealt with each double-page spread. Sometimes they turned out eerily similar and other times totally different. The latter cases were the most interesting, of course. The end result was our book Kaninkostymen (‘The Rabbit Costume’, 2015).

It was brilliant to be able to see the translations that people did of my book Måntornet (‘The Moon Tower’, 2014). So many variations. So many possibilities. Some of the translations made me want to revise the Swedish text, because I thought the translation was better than what I had written myself. That’s because whatever the case, I surprise myself all too seldom. I get stuck in old thought patterns. Having access to so many new ways of interpreting a text was hugely inspiring. I’ve always regarded myself as an illustration person. I’ve never been as interested in texts as I am in images. But after my days in London where everything revolved around words, sentences and meanings, I’ve had a textual awakening. I see the texts I’m working on now in a new light. And that’s really inspiring.

*****

Cilla Naumann is one of five award-winning Swedish authors who travelled to London in early November for a day of practical translation workshops and discussions with SELTA members, other translators and postgraduate students. In one of the workshop sessions, participants compared their translations of an extract from Cilla’s young adult novel 62 dagar (‘62 Days’), published in 2011, and discussed the differences in word choice and textual interpretations that emerged from the various translations. Cilla Naumann’s blog post has been translated into English by SELTA member Nichola Smalley.

On 6 November I left a freezing and snowy Stockholm

– and went out in London’s sunshine and into SELTA’s concentrated world.

What’s a ‘tuva’[1]? And what’s a ‘pir’ – jetty or breakwater?

And the squirrel’s tail – how gruesome can it be?

And why all these compound colour nuances? Is ‘vitgrå’ more grey or more white?

And that little word ‘ju’ just can’t be translated. It has to be left in the sentence as is –

right?

On the plane home my unconscious word choices whirring round my head – why did I write this and not that?

And what was that thing about ‘spyflugor’[2] – how could I write green-blue when ‘shimmering’ is so much better?

Hear it: ‘skimrande gröna’. What beautiful Swedish!

Then I dozed off and awoke in Stockholm and the snow was all gone.

Thank you SELTA for two intensive, reflective, productive, fun days.

[1] a clod? a clump? a tussock?

[2] bluebottles/blowflies

*****

An ethnologist by training, Annelis Johansson was twice nominated for the August Prize for Young Writers, a national award for promising Swedish writers aged 16–20. She made her publishing debut with Fågelungar (‘Baby Birds’), a young adult novel, in 2007 and followed that up with two more YA novels. Her most recent book, Herr Fikonhatt och slottet Thoufve (‘Mr Fighat and Castle Thoufve’), just out from Opal in September 2014, marks a new direction in Annelis’ writing as it is aimed at slightly younger readers. The English translation here is by Agnes Broomé.

It’s been a week since I and four other Swedish authors had the honour of participating in SELTA’s Literary Translation Seminar and Workshop in London. Outside the sky is low and grey; the Swedish autumn has descended on us, making it difficult to remember that there even is a sun. It’s back to the grind of everyday again, and my inspiration is sealed away inside the memory of green leaves, brighter days and a body trembling with the joy of spring.

Back in the slow November rhythm of my small town, London feels very far away. Winter is almost here and it’s time to hibernate. I actually think I do my best writing in winter. It’s as though my longing to live breathes life into my words and it’s in the mild light of reflection my stories develop and grow wings.

“It’s a gorgeous day!” my boyfriend exclaims when we wake up and look out the window. His words contain no hint of irony, and suddenly I see the cold, bare trees anew. This is the way November expresses itself. Why not? November has a story to tell too.

We go to the library for some inspiration and to feel the power of the thoughts and words hidden there. My boyfriend studies, reading a text about cures for HIV, and I sit here contemplating words. Words that hold so many things. To be honest, there are days when I can’t make myself go to the library. On occasion I’ve made it here only to immediately leave again. It’s as though the power of the words and the thoughts locked inside them is an energy that sometimes knocks me over. And yet, there are so few of them. Because really, who among us can say there is a language able to explain everything? What sound does a budding wood anemone make when it bends in the breeze, and who can describe what it feels like when the forest hums and tingles and you’re struck by the enormity of the fact that something has existed for aeons of time, while you yourself have only been drawing breath for a fleeting moment. Sometimes I have enviously wished I worked with music, not words, because I somehow believe that notes can speak where words fail. That there is a language beyond words. And yet, words are what I choose to surround myself with.

At SELTA’s seminar the other week it was brought home to me that Swedish is a feeble language. It’s been said that people get terser the further north you go, but it suddenly seemed so ridiculous to me that we northern people have so few nuances to describe the world around us, while the English language seems to be an endless well to draw on. I snuck in during the conversation between a group of translators and the Swedish illustrator and author Per Gustavsson. A lively debate was under way about how to translate the Swedish word “skog”. The contenders seemed to be “forest” or “wood”. The discussion centred on whether a “forest” is darker and scarier than a “wood” and I asked whether maybe a “forest” might be evergreen while “wood” could be predominantly deciduous.

We journeyed on through the text, pausing at the translation of the expression “simsalabim”. Someone had used a brief English rhyme that neither Per nor myself had heard and it seemed like the English language had several different ways of describing a sudden and somewhat surprising event that still falls well short of Harry Potter magic. Per looks to me for support and asks if I can think of an expression for an event of that kind in Swedish, but despite desperate efforts, nothing comes to mind. “Maybe we’re not that magicky in Sweden,” I put in hesitantly, and we share a laugh. The Swedish language feels inadequate. Someone suggests “tada!” and we smile again, because even though “tada!” might be as close as Swedish can get, it doesn’t quite feel like a word; it’s more of a sound. Like something from a speech bubble in an old comic book.

A few hours later it’s time for my own workshop, and I have used the word “rumpa” in my text. The translators put forward a range of suggestions on how to phrase that in English. Words like “bum”, “ass”, “bottom” and “arse” featured. “Bum” is the popular favourite. I have no idea which one is more suitable. We have several words for “rumpa” in Swedish too, but the difference in register of “röv” or “arsle”, for example, seems so great there’s really no need to discuss them. Especially in the context of a children’s book. “Röv” is not a word you often hear coming out of children’s mouths.

The discussion was long and lively and at this very moment, when I’m writing this and realise that I keep reverting to the present tense to express myself, I remember that somebody told me that English children’s books are almost always written in the past tense. As though the past tense sets the right mood for a story and that rich language exists to bring memories to life. A story told in the present tense doesn’t contain within it the considered reflections of the narrator; it bounces along in the here-and-now, with little time for verbosity. Maybe that’s why we’re so feeble in Sweden? Events are habitually retold in the present tense, where memory hasn’t had a chance to add brighter shades to the colours and sharpness to the details. It’s like November. The sea is never bluer, the fields never more golden and the trees never more beautiful than in November. When it happens, when life is in the present tense, those short weeks when the banks of the river are covered with wood anemones, when you’re busy just being and wondering at the enormity of spring returning, year after year, the joy and exultation comes out as a delighted “ahh”. Or “guuuud, vad härligt!” or the almost fully English “shit, vad najs!”. Swedified English loanwords that sound innovative and international but maybe express nothing so much as our inability to put our thoughts into apposite words.

I think about language more and more. I think about how words are tools that make it possible for us to express our inner selves to the outside world. To make ourselves better understood.

A little girl, maybe one year old, has been watching us while we sit reading and writing. She observes, delighted, and her eyes are more alive than ours. She doesn’t have any words yet. Even so, she’s happy and alive, and yet we know that she, like the rest of us, will spend her life mastering language. It’s through words she will explore life and herself.

I’m grateful that I was given the chance to participate in SELTA’s seminar. Grateful to have realised how adept the English language is at expressing exactly what needs to be said, and how impressed I am by all the translators and their ceaseless efforts to strike the right note when words are transformed on their journey to a new country. Imagine, if I had been born in the UK instead! Then I would have had a richer palette to work with. Then my word-painting could have been even more subtle.

“Do you want to go for a fika?” my boyfriend asks, and I look up and smile. Fika would be good. Because when all’s said and done, I’m Swedish. And we always go for fika. So I wrap things up, turn my mind to other things, and finally admit to myself that ultimately, it might be a good thing that I don’t have to make a decision every time I think about “skog” or “rumpa”.

After a lovely lunch and some good chats among the participants, the afternoon session kicked off with Kayo Mpoyi and Joel Mauricio Isabel Ortiz introducing us to their work. Kayo’s “Mai Means Water” is based upon the myths told in her family, while Joel’s “A Story of a Son” is an exploration of how bad things can get and is definitely not autobiographical. The following workshops with the authors provided valuable feedback about how they as authors would like to see their work presented in another language and how, as a translator, you can sometimes set off on the wrong track and only realise it right at the end.

After a lovely lunch and some good chats among the participants, the afternoon session kicked off with Kayo Mpoyi and Joel Mauricio Isabel Ortiz introducing us to their work. Kayo’s “Mai Means Water” is based upon the myths told in her family, while Joel’s “A Story of a Son” is an exploration of how bad things can get and is definitely not autobiographical. The following workshops with the authors provided valuable feedback about how they as authors would like to see their work presented in another language and how, as a translator, you can sometimes set off on the wrong track and only realise it right at the end.

We were lucky enough to secure a slot in the Free Word Centre’s Wanderlust programme of international literary events. Their ‘speed book clubbing’ format was ideal for giving audience members an opportunity to hear all four authors speak about their work up close. Everyone was seated at four round tables. The authors, each accompanied by a SELTA member who had translated a brief extract from one of their works, introduced themselves and their writing and responded to questions and comments from the group. After around 20 minutes a bell rang out, signalling it was time for the authors and translators to move to the next table and meet a new group of readers. The dynamic format kept interest levels high, and eventually all the groups had a chance to engage with each of the visiting authors. If you missed this exciting event – tickets sold out well in advance! – you can still get a sneak peek at the pieces that were specially translated for the evening on the Free Word Centre website.

We were lucky enough to secure a slot in the Free Word Centre’s Wanderlust programme of international literary events. Their ‘speed book clubbing’ format was ideal for giving audience members an opportunity to hear all four authors speak about their work up close. Everyone was seated at four round tables. The authors, each accompanied by a SELTA member who had translated a brief extract from one of their works, introduced themselves and their writing and responded to questions and comments from the group. After around 20 minutes a bell rang out, signalling it was time for the authors and translators to move to the next table and meet a new group of readers. The dynamic format kept interest levels high, and eventually all the groups had a chance to engage with each of the visiting authors. If you missed this exciting event – tickets sold out well in advance! – you can still get a sneak peek at the pieces that were specially translated for the evening on the Free Word Centre website. We then split into two groups to analyse and discuss a bundle of translations that participants had prepared of a brief extract from Elin and Therése’s most recent novels. Looking at multiple English versions of a single source text highlights the differences between individual translators’ interpretations and word choices. It also gives us translators a chance to really geek out about fine shades of meaning and to expand our range of translation strategies, learning from the solutions chosen by our colleagues. Elin Olofsson has shared her own reflections on her group’s workshop discussion in a guest post.

We then split into two groups to analyse and discuss a bundle of translations that participants had prepared of a brief extract from Elin and Therése’s most recent novels. Looking at multiple English versions of a single source text highlights the differences between individual translators’ interpretations and word choices. It also gives us translators a chance to really geek out about fine shades of meaning and to expand our range of translation strategies, learning from the solutions chosen by our colleagues. Elin Olofsson has shared her own reflections on her group’s workshop discussion in a guest post. Then it was time to listen to a panel of UK editors who shared their experiences of publishing nature-related books in translation and what they look for in a book when commissioning. Saskia Vogel of SELTA moderated the panel discussion with Laura Barber of Portobello Books, Katharina Bielenberg of MacLehose Press and Luke Neima of Granta Online.

Then it was time to listen to a panel of UK editors who shared their experiences of publishing nature-related books in translation and what they look for in a book when commissioning. Saskia Vogel of SELTA moderated the panel discussion with Laura Barber of Portobello Books, Katharina Bielenberg of MacLehose Press and Luke Neima of Granta Online.

ywhere close to. They might not always have been better. But just the fact that they were new ways of looking at the problem was inspiring.

ywhere close to. They might not always have been better. But just the fact that they were new ways of looking at the problem was inspiring.