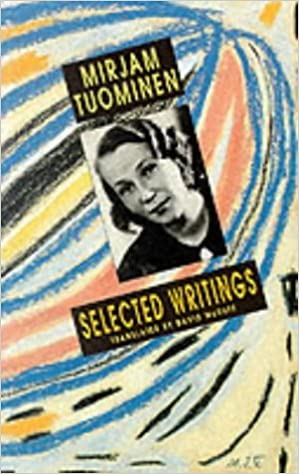

A selection of poetry and prose by Mirjam Tuominen, one of the trio of great Nordic women poets, along with Edith Södergran and Karin Boye..

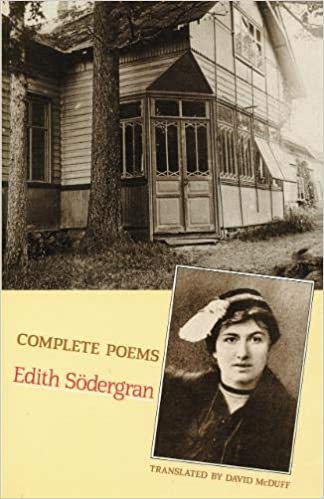

Mirjam Tuominen was a major poet and short story writer, as well as a distinguished essayist, translator and artist. Her work progressed through traditional prose, modernist poetry and abstract painting to Roman Catholic mysticism. She is one of the trio of great Nordic women poets, along with Edith Södergran and Karin Boye – all three published in English by Bloodaxe Books.

Her stories are often about love’s intensity, its eroticism and tenderness, about jealousy and struggles for power between men and women. They are acute in their depiction of small town life in Finland in the 1940s, and in capturing her sense of dread at the alarming upsurge of Nazi sympathies during the War. Everything she wrote afterwards was scarred by the horror of the Holocaust, and in particular by one news story of a German soldier who threw a Jewish boy into a sewer because the boy cried when the soldier was whipping his mother. Tuominen had a frightening, self-destructive ability to react directly to the suffering of others, and much of her poetry can be traced back to her anguished response to this one incident. Her poems are obsessive in confronting guilt, vulnerability and power, in their searching for absolute truth in a world she saw as split between victims and tormentors.

Tuominen was drawn to writers who were vulnerable and tormented outsiders. She translated their work, and wrote powerful studies of figures such as Kafka, Rilke, Proust, Hölderlin and Cora Sandel. Her essays shows the extent of her identification with them: ‘Kafka must have felt the conflict between the demands of his inner being and those of the world around him with an extreme and almost intolerable intensity.’

David McDuff’s edition includes selections from Mirjam Tuominen’s poetry and stories, as well as her seminal essay Victim and Tormentor. The book is introduced by her daughter, the writer Tuva Korsström.