Photos by Ian Giles.

Sarah Death writes:

The recent SELTA translation workshop, held at the Swedish Embassy in London at the kind invitation of the cultural counsellor and her team, was the brainchild of former chair Ruth Urbom and brought to fruition by her hard work, with the help of Chair Ian Giles and the SELTA committee. The theme of the event was working-class writers and our four guests from Sweden introduced themselves and their work before we broke into author-led groups to take a closer look at the extracts we had prepared and the many and various solutions we had found.

I was part of the group that enjoyed a very fruitful session working with author and critic Anneli Jordahl, who has a long catalogue of titles to her name, both fiction and non-fiction. She is a critic and reviewer for the Swedish papers Aftonbladet, Expressen and Sydsvenska Dagbladet and has won numerous literary prizes.

As has become customary at SELTA workshops, those who had done the translation in advance – including members who could not attend – had sent in their work, and thanks to the organisers we had in front of us an anonymised array of English versions to inform our discussion. When a group of literary translators assembles to work on a text they have prepared, the discussions can be quite intense, detailed and niche, but having the author there always leads to more insightful and rewarding work, and Annneli was such an engaging collaborator.

We worked with her on an extract from her recent, book-length essay Orm med två huvuden (2019, Snake with Two Heads) in which she casts an appraising eye on her own background and its impact on her dual – and sometimes conflicting – roles as an author and a critic. For someone from her background to be accepted as a critic, she told us, it was a real struggle. The extract we tackled was from a section in which the young Anneli becomes a latchkey kid and discovers her appetite for books and the joy of libraries and solitary reading.

The first challenge hit us in the very first sentence. Anneli’s parents lived in a ‘Mexitegelvilla’, house of a type that has become pretty much synonymous with the optimistic and aspirational spirit of Sweden in the 1970s. The building material, ‘Mexitegel’ is a shimmering kind of white brick and the ‘villa’ is nothing like the Mediterranean image that this might conjure up for a British reader but simply a standard, free-standing Swedish domestic residence. Yet how to encapsulate all this and convey all those associations with a simplicity that comes anywhere near that of the single word in the original Swedish? None of our versions could really do it full justice.

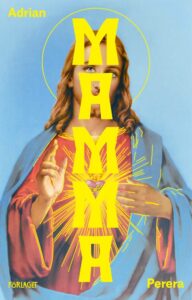

Anneli’s father was an electrician and her mother worked in a restaurant. She writes of them as ‘pappa’ and ‘mamma’, which seems simple enough, but these words are perennially problematic for translators into English in terms of register and cultural connotations. Take ‘mamma’, for example. We discussed leaving it unchanged, but does it sound a little too much like a child’s exclamation? Eventually we concluded that all solutions had their drawbacks. ‘Mama’ has too Victorian a flavour, doesn’t it? Is ‘Mum’ too British and ‘Mom’ too American? Does ‘Mummy’ sound too childish, or too upper-middle-class British? Anneli gave us some interesting background information: in Sweden there were, and perhaps still are, regional variations. In Skåne, your parents would be known as ‘mor och far’, whereas in Dalarna they would be ‘mamma och pappa’.

Anneli’s father was an electrician and her mother worked in a restaurant. She writes of them as ‘pappa’ and ‘mamma’, which seems simple enough, but these words are perennially problematic for translators into English in terms of register and cultural connotations. Take ‘mamma’, for example. We discussed leaving it unchanged, but does it sound a little too much like a child’s exclamation? Eventually we concluded that all solutions had their drawbacks. ‘Mama’ has too Victorian a flavour, doesn’t it? Is ‘Mum’ too British and ‘Mom’ too American? Does ‘Mummy’ sound too childish, or too upper-middle-class British? Anneli gave us some interesting background information: in Sweden there were, and perhaps still are, regional variations. In Skåne, your parents would be known as ‘mor och far’, whereas in Dalarna they would be ‘mamma och pappa’.

Anneli’s mother worked for many years at ‘Stadshotellet’ (traditionally the leading hotel in a town) where her job description in Swedish was ‘kallskänka’. There is a great deal to unpack in this word before one can even think of trying to find an appropriate translation. Various dictionaries offered us the term ‘cold-buffet manageress’, which sounds like someone who takes bookings, shows people to their tables and makes sure the buffet platters are replenished; but the title also has that slight managerial ring. Anneli explained that in reality it was a job with quite a lowly place in hierarchy but requiring considerable artistic skills. It involved not only arranging all those eye-catching platters of smorgåsbord essentials but also constructing the smörgåstårta, the staple of summer Swedish catering: essentially a party-sized cut-and-share club sandwich, full of seafood and other layers, all held together with mayonnaise and beautifully decorated with unshelled prawns and fronds or flower-heads of dill. How could we render all this cultural context in English? In the end, reluctant to overload the sentence, we decided to make do with the rather underwhelming phrase ‘running the lunch buffet’.

Moving on to how Anneli was expected to behave as a child, we read in our text that her mother thought it safest in social terms for her largely to be seen and not heard, but – as was quite common at that period – she would sometimes be expected to niga, that is, to curtsey, to important guests. We had an entertaining interlude in which full, deep curtsey (called a hovnigning or court curtsey in Swedish, Anneli told us) was demonstrated by one of our number, but decided that for a young girl we would probably use ‘bob’ or ‘give a bob’, as long as we were sure the context made it clear what was going on.

In the next section Anneli described the gloriously indiscriminate reading of her childhood, everything from Asterix to Jules Verne – ‘från A till Ö’, as Anneli’s text put it, which in English surely has to become A to Z? We were faced with putting the extensive lists into succinct English, and not cramming them to full of explanatory detail. One example was Vilhelm Moberg’s ‘Utvandrarromaner’, his quartet of novels (1949-59) set in the 1850s, when hardship and hunger forced waves of emigration from Sweden to North America. In these days when readers can look up anything online in a trice, is it all right simply to say ‘the Emigrant novels by Vilhelm Moberg’?

The discussion turned to the general importance of local libraries in both Britain and Sweden for educating and inspiring children. Many Swedish working-class writers have described their vital function in less-privileged childhoods, underpinning many a subsequent class journey. Anneli told us about a successful – and rather touching – modern-day initiative in a library in her own area. Children who are too nervous and intimidated to read out loud in class can go there to read to Book Dog, a trained dog who sits and listens as they read. The scheme has boosted the confidence of many young readers.

The perfect conclusion to our wide-ranging discussions was the group’s wholehearted applause for Anneli’s enthusiastic participation, and also for the fact that she now has the job of her dreams. When young Anneli wistfully enquired whether there was a job she could do in adulthood that would allow her to keep her nose in a book all day, her mother of course said no. But now, she jokes, the majority of her work as a critic and reviewer does indeed involve lying on the sofa, reading!

Kathy Saranpa writes:

On Thursday, October 21, around 20 participants, including authors and guests, assembled at the Swedish Embassy in London in a bright and pleasant room facing the courtyard. After hanging up our coats, signing in, disinfecting our hands, and putting on our masks, we were greeted most warmly by our hosts, Ruth Urbom and Ian Giles, and by a welcome table of coffee, tea and treats. We had a fully packed day ahead of us, and Ruth and Ian kept us on schedule in a very gracious and efficient manner. Ruth explained to us how she had happened to choose the topic of working-class writers, giving us a look at her own background as a log chopper’s assistant. (You’ll have to ask her for the correct term – and terminology was definitely one of the issues surrounding the day’s topic.) She had also noticed that there was a festival of working-class writers scheduled in Bristol on October 22, and worked behind the scenes to enable four Swedish writers to attend. What a terrific opportunity for us!

Susanna Alakoski introduced herself and her ‘klassresa’, another theme for the day, noting that she was 17 before she set foot in a library. Otherwise, those places were far too fine for someone like her. Her first story, ‘Pärs första fisk,’ was the result of her having found a fresh (?) cod, passing it off at home as edible and not eating the soup made from it in case she had to take care of sick family members. She spoke of her very difficult childhood and the struggles she had as a ‘finnjävel’ – another thread that returned with the next speaker, Eija Hetekivi Olsson. She grew up in a rough Gothenburg suburb, Angered, and brought home the grim reality of working-class families almost from the beginning of her remarks: The most segregated city in Europe, Gothenburg features a difference in life expectancy of 30 years between those living in the most affluent areas and those living in Angered. Eija never expected to live very long, so she began writing about her experience in letters to her two daughters – which became books.

After the introductions to these two authors, we split up into two groups. I participated in the session with Susanna Alakoski. The issues we worked on dealt primarily with vocabulary (skiftflicka: doffer? shift girl?; trådrullar: bobbins? spools, reels? and the like) but also tricky citation issues such as the folk song ‘spinn min flicka spinn’ and the quote from Merrie England. What do you do when you don’t have the original text – translate it yourself? We spent a lot of time also simply enjoying the fact that we were working with a real author in real time! It became clear that both professions require a lot of research, but also that translators and authors don’t always have the same priorities or the same amount of power.

After the introductions to these two authors, we split up into two groups. I participated in the session with Susanna Alakoski. The issues we worked on dealt primarily with vocabulary (skiftflicka: doffer? shift girl?; trådrullar: bobbins? spools, reels? and the like) but also tricky citation issues such as the folk song ‘spinn min flicka spinn’ and the quote from Merrie England. What do you do when you don’t have the original text – translate it yourself? We spent a lot of time also simply enjoying the fact that we were working with a real author in real time! It became clear that both professions require a lot of research, but also that translators and authors don’t always have the same priorities or the same amount of power.

We were served a scrumptious, generous lunch along with a well-needed one-hour break for some fresh air out from behind masks. Then the afternoon session began with Anneli Jordahl introducing herself. She explained that she had taken a translation exam once but failed miserably because she had stuck too close to the text (sigh. Weren’t we all there once upon a time?). So she expressed her admiration for what we do. Her “klassresa” began when she got the keys to a library – as a cleaning woman. But she had access to all of those books and, like her character in Ormen med två huvuden, she read indiscriminately – as she explained later, her parents did not hierarchize her reading for her. Next, Mats Jonsson introduced himself as growing up as the only child in his village in Norrland – his best friends were elderly people, who often told him stories, and he credits them for giving him a sense of narrative. He read many comic books as a child and found that this was a genre he could express himself well in – and that they weren’t just for ‘barn och debila’.

I found myself in Anneli Jordahl’s session afterwards. Our first stumbling block was a brick – ‘mexitegel’. How on earth do you express all of the connotations of this word without using a run-on sentence? Another tricky single-word conundrum was ‘skönt’, the word the main character uses after telling the reader that she’s a latchkey child (latchkey was a unanimous choice for ‘nyckelbarn’). Great? Nice? We agreed there was ambiguity in this word until you got to the next sentence. Do you make things easier for the reader, or provide the same degree of vagueness? Other words we talked about were ‘skönlitteratur’, ‘niga’ (which elicited a lovely curtsey from Annie Prime!), ‘ensamförsörjande’, ‘surminen’, and the quotation from Kristina Lugn about indiscriminate reading. We also had some general discussion about translation and writing – having a real-live author there made it difficult to stick strictly to the text. But I suspect that was just fine.

I found myself in Anneli Jordahl’s session afterwards. Our first stumbling block was a brick – ‘mexitegel’. How on earth do you express all of the connotations of this word without using a run-on sentence? Another tricky single-word conundrum was ‘skönt’, the word the main character uses after telling the reader that she’s a latchkey child (latchkey was a unanimous choice for ‘nyckelbarn’). Great? Nice? We agreed there was ambiguity in this word until you got to the next sentence. Do you make things easier for the reader, or provide the same degree of vagueness? Other words we talked about were ‘skönlitteratur’, ‘niga’ (which elicited a lovely curtsey from Annie Prime!), ‘ensamförsörjande’, ‘surminen’, and the quotation from Kristina Lugn about indiscriminate reading. We also had some general discussion about translation and writing – having a real-live author there made it difficult to stick strictly to the text. But I suspect that was just fine.

We reconvened after another coffee break and summarized the day. One of the students remarked that she had had no idea of the complexity of literary translation – but she did not seem scared away. Ruth Urbom thanked the Swedish Embassy, the Swedish Literary Exchange, and the authors themselves. When she first thought of creating this workshop, she had four authors in mind and then listed the ones she would contact if she couldn’t get her top 4. She revealed that her top 4 were sitting there with us. Every one of them had said ‘yes’.

As a new member of SELTA, I was simply blown away by the opportunity to compare translations with colleagues, and equally by the kindness, the humor and the skill they all displayed. I even got an ‘inside’ glimpse of what Brexit has meant in a chat with Ian, and some great tips for places to go on this first trip to London from Henry. I will definitely make this trip again for a future workshop.

Anna McGroarty writes:

At the end of October, I had the pleasure of attending the SELTA translation workshop on working class literature at the Swedish Embassy in London. This was my first SELTA event, and I enjoyed it immensely. I think everyone present was thrilled to finally be able to get together in person again. Having the opportunity to discuss translation choices, difficulties, and ideas with colleagues in person was a hugely rewarding experience. We were also incredibly lucky to have the authors of the books being workshopped with us on the day, giving interesting presentations on their works and backgrounds and participating in our discussions.

In the afternoon, my break-away group chose to focus on an excerpt from Mats Jonsson’s graphic novel Nya Norrland. As most of us had no previous experience of translating this type of text, we were all curious to find out more not only about the craft of translating comics, but also the process of writing and publishing them. We learned plenty from Jonsson who, in addition to having published several highly successful graphic novels, also spent many years working as an editor at Galago, one of Sweden’s largest graphic novel imprints.

Much of our subsequent discussion centred on the difficulties and peculiarities that a text of this nature presents for the translator. Jonsson made the point that the translation of a graphic novel is a whole other animal; one that arguably has more in common with subtitling than with ‘classic’ literary translation, chiefly due to the paramount issue of space. Unless it is possible to increase the size of the text boxes and speech bubbles (usually the task of the letterer, a further person with whom the translator may need to interact over the course of the translation process), the translated text needs to fit in the space allocated to the original in the corresponding text box. Given that text volume tends to expand in translation from Swedish into English, this creates an obvious dilemma, similar to that faced by subtitlers.

Much of our subsequent discussion centred on the difficulties and peculiarities that a text of this nature presents for the translator. Jonsson made the point that the translation of a graphic novel is a whole other animal; one that arguably has more in common with subtitling than with ‘classic’ literary translation, chiefly due to the paramount issue of space. Unless it is possible to increase the size of the text boxes and speech bubbles (usually the task of the letterer, a further person with whom the translator may need to interact over the course of the translation process), the translated text needs to fit in the space allocated to the original in the corresponding text box. Given that text volume tends to expand in translation from Swedish into English, this creates an obvious dilemma, similar to that faced by subtitlers.

The group immediately noted that some tough decisions would have to be made. What needs to be retained to stay true to the original and tell the story, and what can be sacrificed? The need for the translator to be pragmatic becomes clear. Similarly, where in a traditional book, the translator might be able to play around with the structure to make the text flow well in English, the graphic novel translator does not have this luxury. The translation must correspond to the illustration panel in which the original text appears in for the story to make sense to the reader. Our group considered that while these issues impose certain limitations on the translator, there is perhaps also a freedom in being allowed to take more liberties with the source text to make the necessary cuts.

These issues aside, the drawings in a graphic novel add a visual element to the translation process and another layer for the translator to interpret in addition to the text. This has its own appeal for readers and translators alike and is part of what makes the format so unique and captivating.

Lily Stewart writes:

I was barely three weeks into my master’s degree studying Translation Studies at UCL when I was presented with the wonderful opportunity to attend SELTA’s annual literary workshop, joining Swedish authors and translators of Swedish literature into English. As a student of the Scandinavian languages and an enthusiast for literary translation in particular, this was a window into the profession that could not be turned down – and at the Swedish Embassy, no less!

In the morning, the authors Susanna Alakoski and Eija Hetekivi Olsson introduced themselves and their work, speaking especially on the theme of ‘arbetarlitteratur’ and of their personal ‘klassresa’ and how class had motivated and moulded their writing. With this context in mind, we then split into groups to discuss our translations of their work.

My group looked at Eija’s text; an extract from her acclaimed 2012 book Ingenbarnsland. Eija had related to us the influence of her own upbringing in the Gothenburg suburbs on her writing; coming from a Finnish migrant family, her mother a cleaner and her friends and peers with few prospects of advancement or even an average life expectancy. This background is very transparent in the text. The dialogue between the two girls in the extract is distinctively in the Gothenburg dialect, with Finnish influence and 1980s slang. This posed a challenge in terms of situating the characters in time and place for an anglophone audience. To relay the equivalent sense, we discussed how we could convey a non-standard working-class dialect without taking it to the extreme of, for example, peppering the dialogue with Geordie slang! Aside from the clear oddity of this approach, we would then be faced with the issue of whether we could make this work for a North American readership, in which case the ‘equivalent’ dialect would again have to be different.

My group looked at Eija’s text; an extract from her acclaimed 2012 book Ingenbarnsland. Eija had related to us the influence of her own upbringing in the Gothenburg suburbs on her writing; coming from a Finnish migrant family, her mother a cleaner and her friends and peers with few prospects of advancement or even an average life expectancy. This background is very transparent in the text. The dialogue between the two girls in the extract is distinctively in the Gothenburg dialect, with Finnish influence and 1980s slang. This posed a challenge in terms of situating the characters in time and place for an anglophone audience. To relay the equivalent sense, we discussed how we could convey a non-standard working-class dialect without taking it to the extreme of, for example, peppering the dialogue with Geordie slang! Aside from the clear oddity of this approach, we would then be faced with the issue of whether we could make this work for a North American readership, in which case the ‘equivalent’ dialect would again have to be different.

Another point of discussion was how we could translate the humorous way the girls talk, with examples such as ‘E du go eller?’ rendered by one translator as ‘Are you off your rocker?’, but again lacking the distinctive humour that the Gothenburg dialect lends. It was suggested that where we must inevitably lose humour from one aspect of the text, we can compensate in other areas of our translation. The girls are raw and rude and we talked about their tone and attitude being important to preserve in translation, but also considered the question of how brash we want to be and the target readers would allow us to be. The mention of a character taking a 100 SEK ‘en hundring’ from their mother also posed a challenge. One clever suggestion was the translation of ‘a tenner’, which carries the same colloquial sense of ‘hundring’ and states the equivalent value, without going as far as to simply render it as the rough conversion of £10, which we all felt would take the setting too far away from Sweden.

Something which particularly struck me was the translators’ reactions to each other’s work and how much everyone seemed to relish the opportunity for collaboration and vigorous discussion which the workshop sparked. Translators were able to compare their work and decision-making processes, and as our translations differed, we discussed at length the justification of our choices and pondered how far a translator can fight to defend their choice. The direct communication with the translators was also invaluable, and it felt wonderfully empowering to be able to ask the author instantly what their intentions had been when we encountered a particularly tricky or ambiguous line!

I have taken so much from the SELTA workshop, and it has not only strengthened my desire to pursue Swedish literary translation but has given me a better sense of how to achieve this. What’s more, everyone I met at the event was so approachable, helpful, friendly, and inspiring, and I would like to thank Ian Giles and Ruth Urbom for organising the workshop and for being so accommodating.

Anneli’s father was an electrician and her mother worked in a restaurant. She writes of them as ‘pappa’ and ‘mamma’, which seems simple enough, but these words are perennially problematic for translators into English in terms of register and cultural connotations. Take ‘mamma’, for example. We discussed leaving it unchanged, but does it sound a little too much like a child’s exclamation? Eventually we concluded that all solutions had their drawbacks. ‘Mama’ has too Victorian a flavour, doesn’t it? Is ‘Mum’ too British and ‘Mom’ too American? Does ‘Mummy’ sound too childish, or too upper-middle-class British? Anneli gave us some interesting background information: in Sweden there were, and perhaps still are, regional variations. In Skåne, your parents would be known as ‘mor och far’, whereas in Dalarna they would be ‘mamma och pappa’.

Anneli’s father was an electrician and her mother worked in a restaurant. She writes of them as ‘pappa’ and ‘mamma’, which seems simple enough, but these words are perennially problematic for translators into English in terms of register and cultural connotations. Take ‘mamma’, for example. We discussed leaving it unchanged, but does it sound a little too much like a child’s exclamation? Eventually we concluded that all solutions had their drawbacks. ‘Mama’ has too Victorian a flavour, doesn’t it? Is ‘Mum’ too British and ‘Mom’ too American? Does ‘Mummy’ sound too childish, or too upper-middle-class British? Anneli gave us some interesting background information: in Sweden there were, and perhaps still are, regional variations. In Skåne, your parents would be known as ‘mor och far’, whereas in Dalarna they would be ‘mamma och pappa’.

After the introductions to these two authors, we split up into two groups. I participated in the session with Susanna Alakoski. The issues we worked on dealt primarily with vocabulary (skiftflicka: doffer? shift girl?; trådrullar: bobbins? spools, reels? and the like) but also tricky citation issues such as the folk song ‘spinn min flicka spinn’ and the quote from Merrie England. What do you do when you don’t have the original text – translate it yourself? We spent a lot of time also simply enjoying the fact that we were working with a real author in real time! It became clear that both professions require a lot of research, but also that translators and authors don’t always have the same priorities or the same amount of power.

After the introductions to these two authors, we split up into two groups. I participated in the session with Susanna Alakoski. The issues we worked on dealt primarily with vocabulary (skiftflicka: doffer? shift girl?; trådrullar: bobbins? spools, reels? and the like) but also tricky citation issues such as the folk song ‘spinn min flicka spinn’ and the quote from Merrie England. What do you do when you don’t have the original text – translate it yourself? We spent a lot of time also simply enjoying the fact that we were working with a real author in real time! It became clear that both professions require a lot of research, but also that translators and authors don’t always have the same priorities or the same amount of power. I found myself in Anneli Jordahl’s session afterwards. Our first stumbling block was a brick – ‘mexitegel’. How on earth do you express all of the connotations of this word without using a run-on sentence? Another tricky single-word conundrum was ‘skönt’, the word the main character uses after telling the reader that she’s a latchkey child (latchkey was a unanimous choice for ‘nyckelbarn’). Great? Nice? We agreed there was ambiguity in this word until you got to the next sentence. Do you make things easier for the reader, or provide the same degree of vagueness? Other words we talked about were ‘skönlitteratur’, ‘niga’ (which elicited a lovely curtsey from Annie Prime!), ‘ensamförsörjande’, ‘surminen’, and the quotation from Kristina Lugn about indiscriminate reading. We also had some general discussion about translation and writing – having a real-live author there made it difficult to stick strictly to the text. But I suspect that was just fine.

I found myself in Anneli Jordahl’s session afterwards. Our first stumbling block was a brick – ‘mexitegel’. How on earth do you express all of the connotations of this word without using a run-on sentence? Another tricky single-word conundrum was ‘skönt’, the word the main character uses after telling the reader that she’s a latchkey child (latchkey was a unanimous choice for ‘nyckelbarn’). Great? Nice? We agreed there was ambiguity in this word until you got to the next sentence. Do you make things easier for the reader, or provide the same degree of vagueness? Other words we talked about were ‘skönlitteratur’, ‘niga’ (which elicited a lovely curtsey from Annie Prime!), ‘ensamförsörjande’, ‘surminen’, and the quotation from Kristina Lugn about indiscriminate reading. We also had some general discussion about translation and writing – having a real-live author there made it difficult to stick strictly to the text. But I suspect that was just fine. Much of our subsequent discussion centred on the difficulties and peculiarities that a text of this nature presents for the translator. Jonsson made the point that the translation of a graphic novel is a whole other animal; one that arguably has more in common with subtitling than with ‘classic’ literary translation, chiefly due to the paramount issue of space. Unless it is possible to increase the size of the text boxes and speech bubbles (usually the task of the letterer, a further person with whom the translator may need to interact over the course of the translation process), the translated text needs to fit in the space allocated to the original in the corresponding text box. Given that text volume tends to expand in translation from Swedish into English, this creates an obvious dilemma, similar to that faced by subtitlers.

Much of our subsequent discussion centred on the difficulties and peculiarities that a text of this nature presents for the translator. Jonsson made the point that the translation of a graphic novel is a whole other animal; one that arguably has more in common with subtitling than with ‘classic’ literary translation, chiefly due to the paramount issue of space. Unless it is possible to increase the size of the text boxes and speech bubbles (usually the task of the letterer, a further person with whom the translator may need to interact over the course of the translation process), the translated text needs to fit in the space allocated to the original in the corresponding text box. Given that text volume tends to expand in translation from Swedish into English, this creates an obvious dilemma, similar to that faced by subtitlers.

My group looked at Eija’s text; an extract from her acclaimed 2012 book Ingenbarnsland. Eija had related to us the influence of her own upbringing in the Gothenburg suburbs on her writing; coming from a Finnish migrant family, her mother a cleaner and her friends and peers with few prospects of advancement or even an average life expectancy. This background is very transparent in the text. The dialogue between the two girls in the extract is distinctively in the Gothenburg dialect, with Finnish influence and 1980s slang. This posed a challenge in terms of situating the characters in time and place for an anglophone audience. To relay the equivalent sense, we discussed how we could convey a non-standard working-class dialect without taking it to the extreme of, for example, peppering the dialogue with Geordie slang! Aside from the clear oddity of this approach, we would then be faced with the issue of whether we could make this work for a North American readership, in which case the ‘equivalent’ dialect would again have to be different.

My group looked at Eija’s text; an extract from her acclaimed 2012 book Ingenbarnsland. Eija had related to us the influence of her own upbringing in the Gothenburg suburbs on her writing; coming from a Finnish migrant family, her mother a cleaner and her friends and peers with few prospects of advancement or even an average life expectancy. This background is very transparent in the text. The dialogue between the two girls in the extract is distinctively in the Gothenburg dialect, with Finnish influence and 1980s slang. This posed a challenge in terms of situating the characters in time and place for an anglophone audience. To relay the equivalent sense, we discussed how we could convey a non-standard working-class dialect without taking it to the extreme of, for example, peppering the dialogue with Geordie slang! Aside from the clear oddity of this approach, we would then be faced with the issue of whether we could make this work for a North American readership, in which case the ‘equivalent’ dialect would again have to be different.

After a lovely lunch and some good chats among the participants, the afternoon session kicked off with Kayo Mpoyi and Joel Mauricio Isabel Ortiz introducing us to their work. Kayo’s “Mai Means Water” is based upon the myths told in her family, while Joel’s “A Story of a Son” is an exploration of how bad things can get and is definitely not autobiographical. The following workshops with the authors provided valuable feedback about how they as authors would like to see their work presented in another language and how, as a translator, you can sometimes set off on the wrong track and only realise it right at the end.

After a lovely lunch and some good chats among the participants, the afternoon session kicked off with Kayo Mpoyi and Joel Mauricio Isabel Ortiz introducing us to their work. Kayo’s “Mai Means Water” is based upon the myths told in her family, while Joel’s “A Story of a Son” is an exploration of how bad things can get and is definitely not autobiographical. The following workshops with the authors provided valuable feedback about how they as authors would like to see their work presented in another language and how, as a translator, you can sometimes set off on the wrong track and only realise it right at the end.

We were lucky enough to secure a slot in the Free Word Centre’s Wanderlust programme of international literary events. Their ‘speed book clubbing’ format was ideal for giving audience members an opportunity to hear all four authors speak about their work up close. Everyone was seated at four round tables. The authors, each accompanied by a SELTA member who had translated a brief extract from one of their works, introduced themselves and their writing and responded to questions and comments from the group. After around 20 minutes a bell rang out, signalling it was time for the authors and translators to move to the next table and meet a new group of readers. The dynamic format kept interest levels high, and eventually all the groups had a chance to engage with each of the visiting authors. If you missed this exciting event – tickets sold out well in advance! – you can still get a sneak peek at the pieces that were specially translated for the evening on the Free Word Centre website.

We were lucky enough to secure a slot in the Free Word Centre’s Wanderlust programme of international literary events. Their ‘speed book clubbing’ format was ideal for giving audience members an opportunity to hear all four authors speak about their work up close. Everyone was seated at four round tables. The authors, each accompanied by a SELTA member who had translated a brief extract from one of their works, introduced themselves and their writing and responded to questions and comments from the group. After around 20 minutes a bell rang out, signalling it was time for the authors and translators to move to the next table and meet a new group of readers. The dynamic format kept interest levels high, and eventually all the groups had a chance to engage with each of the visiting authors. If you missed this exciting event – tickets sold out well in advance! – you can still get a sneak peek at the pieces that were specially translated for the evening on the Free Word Centre website. We then split into two groups to analyse and discuss a bundle of translations that participants had prepared of a brief extract from Elin and Therése’s most recent novels. Looking at multiple English versions of a single source text highlights the differences between individual translators’ interpretations and word choices. It also gives us translators a chance to really geek out about fine shades of meaning and to expand our range of translation strategies, learning from the solutions chosen by our colleagues. Elin Olofsson has shared her own reflections on her group’s workshop discussion in a guest post.

We then split into two groups to analyse and discuss a bundle of translations that participants had prepared of a brief extract from Elin and Therése’s most recent novels. Looking at multiple English versions of a single source text highlights the differences between individual translators’ interpretations and word choices. It also gives us translators a chance to really geek out about fine shades of meaning and to expand our range of translation strategies, learning from the solutions chosen by our colleagues. Elin Olofsson has shared her own reflections on her group’s workshop discussion in a guest post. Then it was time to listen to a panel of UK editors who shared their experiences of publishing nature-related books in translation and what they look for in a book when commissioning. Saskia Vogel of SELTA moderated the panel discussion with Laura Barber of Portobello Books, Katharina Bielenberg of MacLehose Press and Luke Neima of Granta Online.

Then it was time to listen to a panel of UK editors who shared their experiences of publishing nature-related books in translation and what they look for in a book when commissioning. Saskia Vogel of SELTA moderated the panel discussion with Laura Barber of Portobello Books, Katharina Bielenberg of MacLehose Press and Luke Neima of Granta Online.

ywhere close to. They might not always have been better. But just the fact that they were new ways of looking at the problem was inspiring.

ywhere close to. They might not always have been better. But just the fact that they were new ways of looking at the problem was inspiring.