February 7, 2024

2023 Bernard Shaw Prize awarded to Saskia Vogel

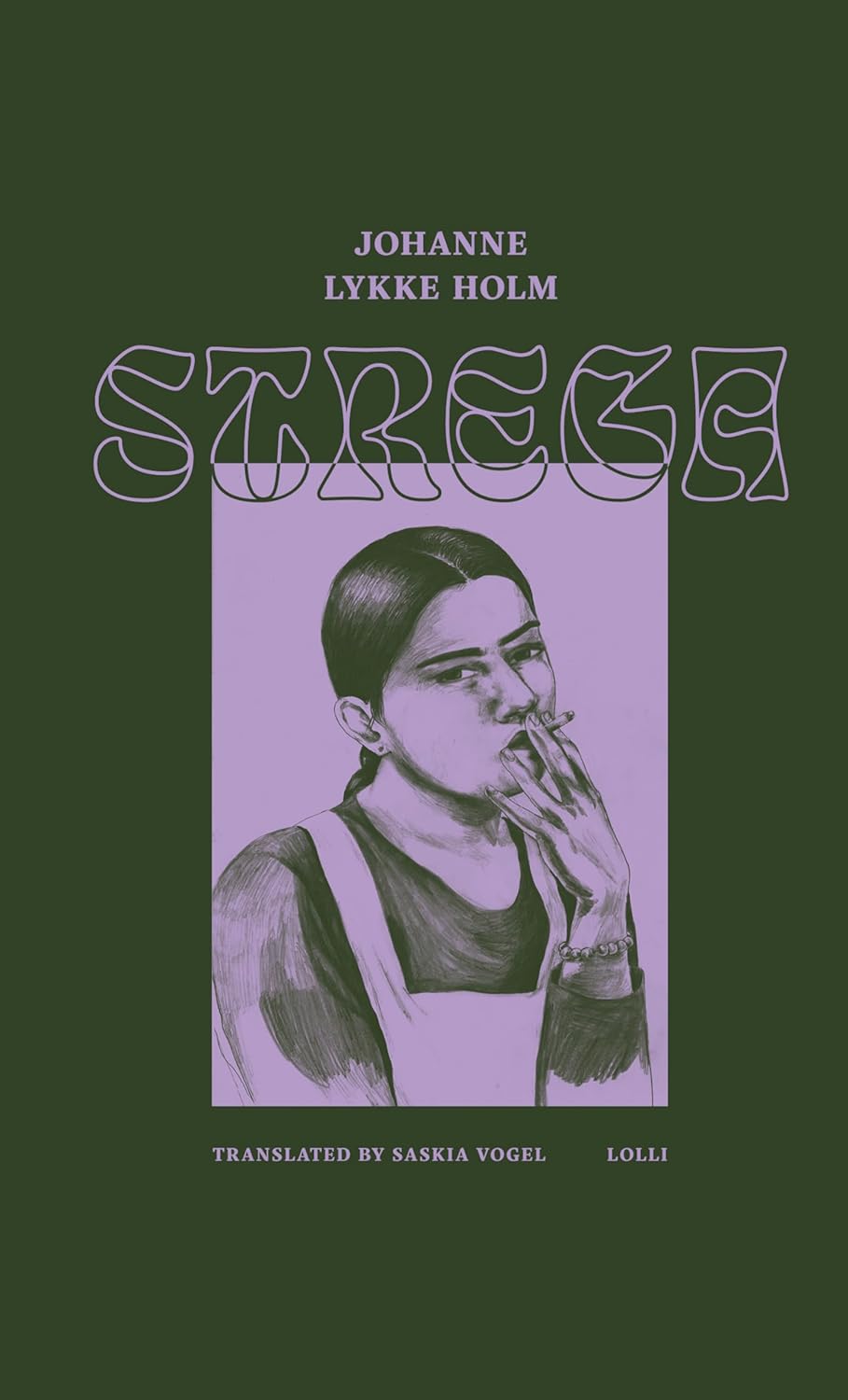

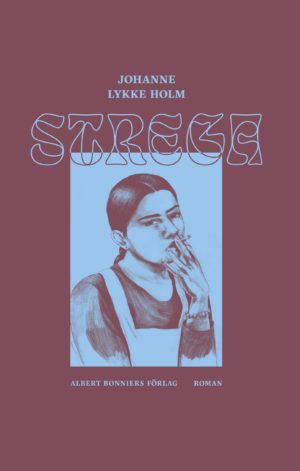

The 2023 Bernard Shaw Prize has been awarded to Saskia Vogel for her translation from Swedish of Johanne Lykke Holm’s ‘Strega’ published by Lolli Editions.

The winner of the 2023 Bernard Shaw Prize is SELTA member Saskia Vogel for her translation of Strega by Johanne Lykke Holm published by Lolli Editions. The winner will be honoured as part of the Society of Authors’ annual Translation Prizes celebratory event held at the British Library on 7th February.

This year’s judges include SELTA member Nichola Smalley, author Amanda Svensson and Guardian journalist and former news editor at The Bookseller Alison Flood, who said of the winner:

‘Johanne Lykke Holm’s story of a girl who arrives to work in an empty hotel in a remote Alpine town is deep and dreamlike, hinting at and then revealing the dark underbelly of growing up as a young woman in a violent society. Saskia Vogel matches the mythlike flavour of Holm’s tale in her luminous translation of this eerie, disturbing novel.’

Nichola Smalley added:

‘Saskia Vogel’s translation of this astonishing novel is truly virtuosic – the text comes alive in all its uncanny beauty as the English language is made to bend supply and excitingly without ever losing its elasticity.’

The runner up was Jennifer Hayashida for her translation of Elin Cullhed’s Euphoria.

The prize is awarded for the best translation into English of a full length Swedish language work of literary merit and general interest, with the winner receiving £3000 and the runner up £1000. Named after the author and dramatist George Bernard Shaw, whose Nobel Prize went towards a foundation for ‘the promotion and diffusion of knowledge and appreciation of the literature and art of Sweden in the British Islands’, the prize was established in 1991 and is generously sponsored by the Anglo-Swedish Literary Foundation and the Embassy of Sweden in London. This marks the first occasion when the prize has been awarded biennially. The next award will be for 2025 (awarded in 2026).

This was the first time that SELTA member Saskia Vogel was shortlisted for the Bernard Shaw prize, while also being the first time Lolli Editions has featured on the shortlist for the prize. SELTA offers its wholehearted congratulations to Saskia on her achievement.

You can watch the full prize ceremony here. And finally well done to all the translators who were featured on the shortlist for the 2023 prize as announced last December.