SELTA Chair Ian Giles sums up 2019 and looks ahead to 2020.

Our membership figures remain strong – there are currently 74 members of SELTA, an increase of 2 over last year. It’s gratifying to see that we continue to attract new members who recognise the benefits that SELTA offers, even in these changing times.

2019 was a relatively busy year for SELTA. I’m sure I wasn’t the only person to find London Book Fair exhausting, not least on the grounds of the considerable number of Swedish-related events that took place. As ever, we were grateful to Pia Lundberg (Cultural Counsellor at the Swedish Embassy in London) for hosting many of us for dinner, and to the Swedish Literature Exchange for covering the cost of admission to Olympia. It was also exciting that the Embassy pursued a new idea in the shape of its reception at the ambassadorial residence for publishers, agents, translators and others involved in the dissemination of Swedish literature to the UK. We have heard that this is likely to be repeated in 2020. I was glad to see so many familiar faces at our spring meeting which took place the day after LBF. There was plenty to discuss, but I think the element that caught the imagination of members was our discussion with invited guests Magdalena Hedlund (Hedlund Literary Agency) and Lena Stjernström (Grand Agency) who told us about their work as literary agents, with a focus on how books come to market abroad and the involvement of translators like us.

As is often the case, things were a little quieter during the summer season. I was fortunate enough to represent SELTA in a roundtable session in Vancouver with Ellen Kythor (Chair of DELT ) and Paul Norlen (President of STiNA) in which we discussed the role of translator networks in promoting Scandinavian books abroad. You can read my blog about the event here. This was (we think) the first time that SELTA and STiNA have appeared together in an official capacity. There was a significant degree of conversation around why we retain two separate organisations, and this was an issue we raised at the AGM in October and subsequently via the Google Group. It seems that as the translation market internationalises, we should continue to discuss and contemplate how we might bring the two bodies closer together.

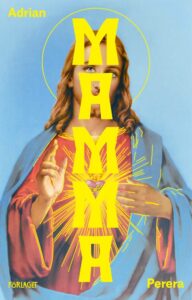

The highlight of SELTA’s year – if I say so – was in late October when we gathered in Edinburgh for our AGM and a literary translation workshop. We had been fortunate enough to receive grants from both the Swedish Arts Council and the Anglo-Swedish Literary Foundation to support this initiative. In particular, I’m delighted at the positive feedback from both funders about not only the type of event we proposed, but also the location and general enthusiasm for translator-led initiatives. We were very pleased to welcome four Swedish-language authors to Edinburgh: Balsam Karam, Kayo Mpoyi, Joel Mauricio Isabel Ortiz, and Adrian Perara. Not only did we have an enjoyable public event – our speed bookclub gathering, but I think we had a very fruitful day-long workshop. It was especially good to see so many new faces in attendance. I appreciated the positive feedback from those who attended – and hopefully we will be able to do something again soon (although perhaps in 2021 to give your Chair some breathing space!).

There was also some exciting news during November when Peirene Press announced that the Peirene-Stevns Prize for 2020 would be in Swedish. At the time of writing, entries are still being accepted from translators of Swedish who have not yet had a full-length literary translation published. The winner will receive a paid commission to translate Andrea Lundgren’s Nordisk fauna as well as a retreat in the French Pyrenees. The winner will be mentored by SELTA member Sarah Death.

SELTA members always tend to do well on the awards circuit and this year was no different. We were thrilled to hear just a week ago that one of SELTA’s founder members, Tom Geddes, has been awarded the Swedish Academy’s ‘pris för introduktion av svensk kultur utomlands’.

This year also saw the award of the 2018 Bernard Shaw Prize, the triennial prize handed to the best Swedish translation. The prize went to Frank Perry for his translation of Bret Easton Ellis and the Other Dogs by Lina Wolff (And Other Stories), while Deborah Bragan-Turner was runner up for her translation of The Parable Book by Per Olov Enquist (MacLehose Press). Indeed, the other two names on the shortlist also came from SELTA’s ranks on this occasion. It has long been the feeling of successive SELTA committees that the prize requires an overhaul. Following in-depth correspondence with Nicola Solomon, the CEO of the Society of Authors (responsible for managing the prize), we engaged in dialogue with various stakeholders about this. While we are already in the cycle for the next prize (to be awarded in 2022), the hope is that the subsequent award of the Bernard Shaw will take place just two years later, and will feature a larger prize fund. Naturally, this is all funding-contingent!

We were all overjoyed for SELTA member Deborah Bragan-Turner, whose translation of Sara Stridsberg’s The Faculty of Dreams was longlisted for the 2019 Man Booker International Prize. This was the first time a Swedish title had made the longlist, and it drew attention to a very worthy book.

This year the CWA Crime Fiction in Translation Dagger (formerly known as the International Dagger) very thoughtlessly didn’t award the prize to a Swedish title, but we were still pleased to see Sarah Death shortlisted for her translation of Håkan Nesser’s The Root of Evil, and Annie Prime longlisted for her translation of Martin Holmén’s Slugger.

Those of you who have attended recent meetings or read the minutes, as well as the emails from Deborah Bragan-Turner, will be aware that times are changing for our journal, Swedish Book Review. You will have received a double issue in the form of 2019:1-2 back in the summer, which was the result of the very hard work put in by Deborah, the team at Norvik Press and all the contributors. Regrettably, this is likely to be the last time a regular print issue is published in this form. A working group was formed in the spring to develop proposals for SBR’s future. We are pleased to have received a one-off grant from the Swedish Arts Council to enable us to overhaul the SBR website with the intention of going fully digital and open access. We are currently in the process of seeking additional funding to support a first issue in the new iteration covering the themes we addressed in our Edinburgh workshop.

In 2020, the London Book Fair remains in its earlier slot of March, and will take place on 10-12 March. Hopefully I will see many of you there for the usual, fruitful networking opportunities the event provides. Cut the Cord are organising a Nordic Theatre Festival in London during March. Similarly, the Stanza poetry festival in St Andrews has a Nordic focus for 2020. Pardaad Chamsaz at the British Library is also organising an event about Nordic comics on Friday 13 March.

We expect to hold our SELTA spring meeting in London in late April or early May (date tbc). More details on this will follow with plenty of notice.

Best wishes for the new year ahead!

Dr Ian Giles

Chair of SELTA

After a lovely lunch and some good chats among the participants, the afternoon session kicked off with Kayo Mpoyi and Joel Mauricio Isabel Ortiz introducing us to their work. Kayo’s “Mai Means Water” is based upon the myths told in her family, while Joel’s “A Story of a Son” is an exploration of how bad things can get and is definitely not autobiographical. The following workshops with the authors provided valuable feedback about how they as authors would like to see their work presented in another language and how, as a translator, you can sometimes set off on the wrong track and only realise it right at the end.

After a lovely lunch and some good chats among the participants, the afternoon session kicked off with Kayo Mpoyi and Joel Mauricio Isabel Ortiz introducing us to their work. Kayo’s “Mai Means Water” is based upon the myths told in her family, while Joel’s “A Story of a Son” is an exploration of how bad things can get and is definitely not autobiographical. The following workshops with the authors provided valuable feedback about how they as authors would like to see their work presented in another language and how, as a translator, you can sometimes set off on the wrong track and only realise it right at the end.

There were a couple of questions from the audience relating to how the process works when applied specifically to translated titles. In general, dealing with foreign literary agents was deemed a rarity (and it was noted that many countries simply don’t have any), with publishers often choosing to look and see what their ‘partner’ publishers abroad were acquiring. None of the panelists had experience with translations, but they had consulted Katharina Bielenberg of MacLehose Press beforehand. The reported response was that many acquisitions were done on the basis of trust and long-term relationships with foreign publishers and authors.

There were a couple of questions from the audience relating to how the process works when applied specifically to translated titles. In general, dealing with foreign literary agents was deemed a rarity (and it was noted that many countries simply don’t have any), with publishers often choosing to look and see what their ‘partner’ publishers abroad were acquiring. None of the panelists had experience with translations, but they had consulted Katharina Bielenberg of MacLehose Press beforehand. The reported response was that many acquisitions were done on the basis of trust and long-term relationships with foreign publishers and authors.

The Swedish-Eglish Literary Translators’ Association (SELTA) was founded in the UK in 1982 and has since served the interests of its members – practicing, professional literary translators – as well as promoting Swedish-language literature to the English-speaking world through its house journal Swedish Book Review. Swedish Translators in North America (STiNA) was established in 2004 to represent the interests of literary translators of Swedish working in the USA and Canada. The Association of Danish-English Literary Translators (DELT) is very much the new kid on the (Scandinavian literary translation) block, having been first established as a network in 2014 before forming a full association in 2018. The three organisations come from different backgrounds, but all fulfil important roles in representing Scandinavian literary culture abroad.

The Swedish-Eglish Literary Translators’ Association (SELTA) was founded in the UK in 1982 and has since served the interests of its members – practicing, professional literary translators – as well as promoting Swedish-language literature to the English-speaking world through its house journal Swedish Book Review. Swedish Translators in North America (STiNA) was established in 2004 to represent the interests of literary translators of Swedish working in the USA and Canada. The Association of Danish-English Literary Translators (DELT) is very much the new kid on the (Scandinavian literary translation) block, having been first established as a network in 2014 before forming a full association in 2018. The three organisations come from different backgrounds, but all fulfil important roles in representing Scandinavian literary culture abroad.