November 2, 2022

SELTA at 40

SELTA is 40 years old in 2022. To introduce our series of interviews with members, we look back over our history as an organisation.

In April 1982, the Swedish-English Literary Translators’ Association held its first Annual General Meeting. In November 2022, we will be meeting to celebrate our 40th anniversary. On the website we are celebrating by interviewing members – founding, longstanding and more recent – about their careers and what SELTA means to them. But first some history.

How it all began

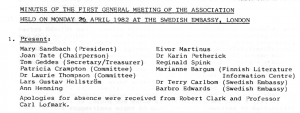

SELTA has always had close links with and support from the Swedish Embassy in London and the first impetus for bringing translators of Swedish together came from cultural attaché Ove Svensson who joined forces with the Swedish Institute and held a conference of translators and publishers at University College London in 1978. In 1981, the next cultural attaché Terry Carlbom arranged a translators’ conference at the University of Hull and in November the same year ran a seminar which led to the setting up of the Swedish-English Literary Translators’ Association the following morning. Original SELTA members who made that initial decision were Patricia Crampton, Tom Geddes, Mary Sandbach, Joan Tate and Laurie Thompson. Thomas Teal was also present but for practical reasons in a pre-internet age it was decided that the aim should be for US translators to form their own association and for the two organisations to work closely together. By the time of the first AGM in April 1982, SELTA had 9 full members and 3 associate members.

SELTA has always had close links with and support from the Swedish Embassy in London and the first impetus for bringing translators of Swedish together came from cultural attaché Ove Svensson who joined forces with the Swedish Institute and held a conference of translators and publishers at University College London in 1978. In 1981, the next cultural attaché Terry Carlbom arranged a translators’ conference at the University of Hull and in November the same year ran a seminar which led to the setting up of the Swedish-English Literary Translators’ Association the following morning. Original SELTA members who made that initial decision were Patricia Crampton, Tom Geddes, Mary Sandbach, Joan Tate and Laurie Thompson. Thomas Teal was also present but for practical reasons in a pre-internet age it was decided that the aim should be for US translators to form their own association and for the two organisations to work closely together. By the time of the first AGM in April 1982, SELTA had 9 full members and 3 associate members.

In Newsletter No. 3 in January 1983, the Secretary reported 36 members, 16 full members and 20 associates. Today, in autumn 2022, we have 82 members, 27 of whom are associates. In terms of fulfilling the aims of our predecessors, we’re not doing badly.

“The more members we have, the stronger the position we shall be in to influence publishers and cultural bodies, and the more we shall be able to do to spread awareness of Swedish literature, promote translation and provide information on current conditions and events in the field of Swedish-English translation.”

Newsletter No. 2 July 1982

Tom Geddes, founder member and long-term secretary/treasurer and also chair of SELTA, wrote SELTA the First 25 Years, covering SELTA’s history up to 2006, including such key events as the founding of the Bernard Shaw Prize for Swedish to English translation in 1991 and a description of SELTA’s book report scheme in which members wrote 434 (unpaid) one-page book reports between 1982 and 1996, 171 of them by Joan Tate. Reading the history, the report of the seminar in 1981 (available to members under Minutes on the Members’ pages) and the early minutes and newsletters provided by Tom, it is fascinating to see how some things have remained the same. Our Secretary no longer has to produce minutes and newsletters on a typewriter and put them in the post – in the accounts for 1983, £112.99 went on postage costs, which was slightly more than the £100 grant from the Anglo-Swedish Literary Foundation – but issues raised at the first seminar included the amount of payments under the Swedish state subsidy scheme for translations of Swedish literature published abroad, the need to ensure the translator was actually paid, and concerns from British publishers at having to pay about £1,500 for a 200 page foreign title with a maximum print run of only 2,000 copies.

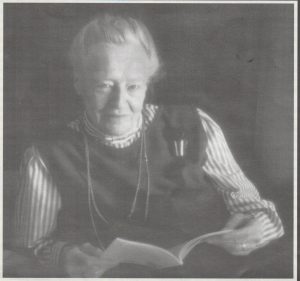

Joan Tate

On the bright side though, we are not currently “lamenting a decrease in the number of translations of literary works published from Swedish and other languages” as Joan Tate was in the early 1980s. At the time, hopes were placed in the rise of feminism as a potential market to be exploited. Nordic Noir was not yet on the horizon. “The continuing Stieg Larsson/Henning Mankell phenomenon” appears as item 9 on the agenda at the AGM in 2009.

Other things have changed. The arrival of the internet brought a website and an email group, giving members a useful channel for translation-related discussions. The first SELTA website was designed by Henning Koch in 2005 and was then managed by Peter Linton. The website was revamped in 2013 and gained a blog section, although getting members to write for it proved more of a challenge. We now have a Twitter account and this year members have been seen reading their translations on YouTube. The current website is the third iteration and went live in 2020 in parallel with a rebrand and a new logo. Instead of the Secretary keeping a record of members to send out to publishers looking for a translator, potential clients can now find us themselves and send a potential job to those of us who have opted in. Same aims, just a different way of achieving them.

Likewise, like the rest of the world, during the pandemic we got to grips with online meetings and ran webinars/online workshops and fikastunder to keep in touch remotely. The committee has since resolved to keep the AGM online to enable greater participation from our more far-flung members, especially in view of the vote at the 2020 AGM to open membership to translators in the US who meet the membership criteria.

In 1981 it was expected that SELTA would hold at least one conference a year. We meet twice a year, once online, but instigated by Ruth Urbom, we also began to run workshops with invited Swedish authors from 2014. See our News pages for reports on these. The News pages also carry reports on members who have won awards, including the aforementioned Bernard Shaw Prize.

In 1981 it was expected that SELTA would hold at least one conference a year. We meet twice a year, once online, but instigated by Ruth Urbom, we also began to run workshops with invited Swedish authors from 2014. See our News pages for reports on these. The News pages also carry reports on members who have won awards, including the aforementioned Bernard Shaw Prize.

In 2013 a discussion paper was issued to members on the future of SELTA, exploring whether the association should be wound up and whether in fact there was a need to meet up in person at all. Those present at the 2013 Spring Meeting decided to carry on, as it was felt that exchanges with real people and fostering a sense of community were still important. In 2022, winding up SELTA seems unthinkable. We are alive and well and still going strong and it is that sense of community that comes through in the pieces by members in honour of our anniversary.

SELTA officers past and present

President: Mary Sandbach (1982–1990)

Chair: Joan Tate (1982–1986); Tom Geddes (1986–1991); Patricia Crampton (1992–1996); Eivor Martinus (1996–2011); Tom Geddes (2011); Anna Paterson (2011–2012); Ruth Urbom (2012–2018); Ian Giles (2018–

Secretary: Tom Geddes (1981–2006); Peter Linton (2006–2010); Martin Murrell (2010–2012); Deborah Bragan-Turner (2012–2015); Nicky Smalley (2015–2016); Saskia Vogel (2016–2020); Alice Olsson (2020–

Treasurer: Tom Geddes (1981–2004); Janet Cole (2005–2016); Ian Giles (2016–2018); Annie Prime (2018–

The current committee also comprises Kate Lambert as Webmaster and Alice Menzies as Minutes Secretary, both roles that first appear in the minutes in 2009. Many more members have served on the committee over the years in other roles or as committee members without portfolio and the introduction of a requirement that two committee members resign every two years, although they can then be re-elected, has resulted in higher committee turnover and brought in new blood.

Swedish Book Review

Swedish Book Review

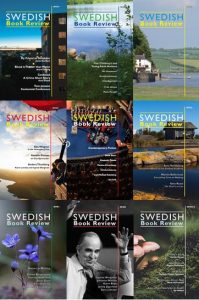

Our journal, Swedish Book Review has been part of SELTA’s efforts from the very start as this quote from 1983 shows:

“In more concrete terms, we have set in motion a number of projects which we hope will come to fruition in this coming year. The most exciting of these is the planned takeover of the journal Swedish Books under the editorship of Dr Laurie Thomspon and the control of an editorial board appointed by SELTA.”

SELTA Newsletter No. 3, 1983

Laurie Thompson not only took over Swedish Books, which was offered to SELTA by its then editors, he edited Swedish Book Review (SBR) from 1983 until 2002. A separate Reviews editor was appointed in 1996 and there were assistant editors in the early 2000s as well as the editorial board. Swedish Book Review continues to showcase Swedish writers, provide independent book reviews of new Swedish books and offer an opportunity for translators to have shorter translated extracts published. Below, Deborah Bragen-Turner writes about the challenges SBR faced during her editorship and the changes recently made.

Swedish Book Review: the years of change

by Deborah Bragan-Turner

By 2015 Swedish Book Review had been thriving in print for 32 years under the inspired and attentive editorship of first Laurie Thompson and later Sarah Death. It continued very successfully to produce independent and impartial reviews and articles in English on recent Swedish books and authors, as well as highlighting older books. It continued to publish the work of established and emerging translators in extracts from an exciting variety of new books and classics. Subscribers continued to represent a very wide-ranging audience, from general readers, publishers and literary agents to academics and students.

By 2015 Swedish Book Review had been thriving in print for 32 years under the inspired and attentive editorship of first Laurie Thompson and later Sarah Death. It continued very successfully to produce independent and impartial reviews and articles in English on recent Swedish books and authors, as well as highlighting older books. It continued to publish the work of established and emerging translators in extracts from an exciting variety of new books and classics. Subscribers continued to represent a very wide-ranging audience, from general readers, publishers and literary agents to academics and students.

However, the situation for translated Swedish literature was changing significantly. With the proliferation of blogs and online journals there was an increasing diversity of ways to find information about new books. The SBR website, which had been created in 1999 by Intexta Web Services and had provided an excellent way of archiving the majority of our content, needed to be updated to keep up with new technology and new ideas. Not only this, but the question of overheads and financial support was a constant concern. As the costs of producing and circulating a printed journal continued to rise, so too did the pressure on our chief sources of funding. While for many the prospect of losing the printed journal was unwelcome, it was clear that for SBR to continue we had to reach a wider audience and generate income ourselves.

After seeking the views of SELTA members, SBR and our publisher Norvik Press submitted a successful application to the Swedish Arts Council in 2019 to fund a new website on which to publish SBR as an online journal. We considered a number of web developers and chose Big Mallet, the company we thought would be the best fit. Big Mallet specialises in charities and not-for-profit organisations and understood the importance of our text-based content and the need for simplicity and clear, attractive typography. They helped us devise a new business model for SBR and ways of raising funds as part of the new digital presence. As the design phase of the project began, so too did the first national lockdown. Our many discussions of the broad design concept and the detail were in the form of emails and video and once the design was agreed, Big Mallet began the work of building the site. In September 2020 members of the SBR team together with two colleagues from Norvik press attended a first Zoom training session on the content management system.

After seeking the views of SELTA members, SBR and our publisher Norvik Press submitted a successful application to the Swedish Arts Council in 2019 to fund a new website on which to publish SBR as an online journal. We considered a number of web developers and chose Big Mallet, the company we thought would be the best fit. Big Mallet specialises in charities and not-for-profit organisations and understood the importance of our text-based content and the need for simplicity and clear, attractive typography. They helped us devise a new business model for SBR and ways of raising funds as part of the new digital presence. As the design phase of the project began, so too did the first national lockdown. Our many discussions of the broad design concept and the detail were in the form of emails and video and once the design was agreed, Big Mallet began the work of building the site. In September 2020 members of the SBR team together with two colleagues from Norvik press attended a first Zoom training session on the content management system.

The aim was to upload not only the eagerly awaited new issue for 2020, but also the material from previous issues available on our old website. Much of the earlier content existed in a form not compatible with new technology and involved reformatting over a thousand different files. Once some of the initial difficulties with input methods had been ironed out by the infinitely patient Big Mallet technical team, we started to work backwards, uploading content from 2020, while they refined the site and finalised the search function. In the late autumn of 2020 the new website launched with a campaign on social media to a very favourable reaction. The new editor, Alex Fleming took over at the helm and has exploited the new system to fill subsequent issues with compelling content, finding innovative ways of engaging with our readers. Work is still going on populating the site with more back issues and increasing our subscriber base. In his interview for SBR in 2020, Tom Geddes, who until 2019 had been a member of the SBR editorial board for 36 years, said he hoped that Swedish Book Review’s new digital future would be “a turn in fortune [ . . .] and well in tune with the times.” While no-one underestimates the work still involved, early indications are very positive!

SBR editors past and present

Swedish Book Review Editor: Laurie Thompson (1983–2002); Sarah Death (2003-2015); Deborah Bragan-Turner (2015–2020); Alex Fleming (2020–

Assistant Editor: Sarah Death (2000–2002); Neil Smith (2003–2010)

Reviews Editor: Irene Scobbie (1996–2000); Sarah Death (2000–2003); Charlotte Whittingham (2003); Henning Koch (2004–2010), Anna Paterson (2010–2015); Fiona Graham (2015–2021); Darcy Hurford (2021–

*****

Now it’s over to our members to tell us about their membership of SELTA, their careers, the varied range of things they translate and how times have changed in the world of Swedish translation since SELTA was founded. Some of our founder members are sadly no longer with us but we have these interviews and tributes.

Joan Tate (1922–2000). A Tribute. SBR 2000:2.

Laurie Thompson (1938–2015). A Tribute from his friends and colleagues. SBR 2016:1. In Memoriam by Marlaine Delargy. SBR 2015:2

Patricia Crampton (1925–2016). Around the World in Sixty Years. SBR 2008:2

*****

Tom Geddes provided this in-depth interview to Deborah Bragan-Turner for SBR 2020:1-2

Eivor Martinus, joined SELTA in 1982

Ann Henning Jocelyn, joined SELTA in 1982

Linda Schenck, joined SELTA in the mid-1980s

Sarah Death, joined SELTA in the mid-1980s

Harry Watson, joined SELTA in the early 1990s

Julie Martin, joined SELTA in 2006

Ian Giles, joined SELTA in the 2010s

Annie Prime, joined SELTA in 2014

Kate Lambert, joined SELTA in 2014

SELTA at 40 by Kate Lambert

Acknowledgements:

Thank you to Tom Geddes for writing the original history of the first 25 years, on which I have drawn for this article, and for providing original minutes and archive material from his time as Secretary, Chair, Treasurer and everything else.

Thank you to Alex Fleming, editor of SBR for permission to use the articles originally published in SBR and for opening up the articles in SBR’s archive.

Thank you to Deborah Bragan-Turner, former editor of SBR, for her contribution on the recent changes to SBR and the cover and website images.

The Swedish embassy image is by Allen Watkin and the SBR website image is courtesy of Nigel Smith, Intexta Services.

A few words about the life of an EFL teacher in Sweden in the far-off days of Olof Palme and Gunnar Sträng (the long-serving finance minister) might be of interest to SELTA members who have followed a more academic route into literary translation. Adult education organisations proliferated in Sweden, some of them affiliated to a particular political party. The Folk University was an exception in that regard, and prided itself on employing only teacher-trained native speakers as teachers of English. Each year between seventy and eighty teachers were recruited from all over the UK on one-year contracts which could be renewed for a further year (a longer stay incurred problems with the tax authorities!).

A few words about the life of an EFL teacher in Sweden in the far-off days of Olof Palme and Gunnar Sträng (the long-serving finance minister) might be of interest to SELTA members who have followed a more academic route into literary translation. Adult education organisations proliferated in Sweden, some of them affiliated to a particular political party. The Folk University was an exception in that regard, and prided itself on employing only teacher-trained native speakers as teachers of English. Each year between seventy and eighty teachers were recruited from all over the UK on one-year contracts which could be renewed for a further year (a longer stay incurred problems with the tax authorities!). But my favours were spread more widely than that, with weekly visits to the neighbouring towns of Finspång (adult evening classes) and Mjölby (admirable gymnasium or high-school pupils staying on for me after the end of the school day). My occasional chauffeur to Finspång (I was and am a non-driver) was an Austrian teacher of German and French who freelanced as a part-time gamekeeper for local aristocrat Grev Douglas (a Swedish count of Scottish descent) and many a trip to Finspång saw us diverting into the local forest so that Norman could check his mink-traps. I took the Malmö train the few miles down to Mjölby and kept up to date with the news from Skåne by browsing discarded copies of Sydsvenska Dagbladet.

But my favours were spread more widely than that, with weekly visits to the neighbouring towns of Finspång (adult evening classes) and Mjölby (admirable gymnasium or high-school pupils staying on for me after the end of the school day). My occasional chauffeur to Finspång (I was and am a non-driver) was an Austrian teacher of German and French who freelanced as a part-time gamekeeper for local aristocrat Grev Douglas (a Swedish count of Scottish descent) and many a trip to Finspång saw us diverting into the local forest so that Norman could check his mink-traps. I took the Malmö train the few miles down to Mjölby and kept up to date with the news from Skåne by browsing discarded copies of Sydsvenska Dagbladet. More recent translations include a biography of the Nobel family and their contribution to the industrialisation of Russia, in which Bloomsbury have expressed an interest, and a biography of J.G. Andersson, a Swedish explorer and geologist who was recruited by the new Republican government in China in 1914 to prospect for mines. In the event, Andersson developed an interest in archaeology and anthropology and ended up helping the Chinese to rewrite their prehistory. This translation still awaits a publisher.

More recent translations include a biography of the Nobel family and their contribution to the industrialisation of Russia, in which Bloomsbury have expressed an interest, and a biography of J.G. Andersson, a Swedish explorer and geologist who was recruited by the new Republican government in China in 1914 to prospect for mines. In the event, Andersson developed an interest in archaeology and anthropology and ended up helping the Chinese to rewrite their prehistory. This translation still awaits a publisher.

From an early age I had one foot in each country and my degree in English (specialising in Literature before 1800) and Litteraturvetenskap at Gothenburg University, which included World Literature, turned out a very good choice for my future career. I was broadly educated in Sweden but moved to this country before I was twenty, finishing my degree here.

From an early age I had one foot in each country and my degree in English (specialising in Literature before 1800) and Litteraturvetenskap at Gothenburg University, which included World Literature, turned out a very good choice for my future career. I was broadly educated in Sweden but moved to this country before I was twenty, finishing my degree here. In Sweden I worked on English classics in my Swedish translations for various theatres: The Shoemaker’s Holiday by Thomas Dekker, The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists by Stephen Lowe and Mad Forest by Carol Churchill.

In Sweden I worked on English classics in my Swedish translations for various theatres: The Shoemaker’s Holiday by Thomas Dekker, The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists by Stephen Lowe and Mad Forest by Carol Churchill.

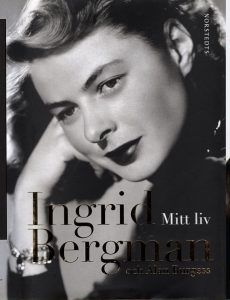

In 1979, I was approached by Norstedts. Ingrid Bergman was writing her autobiography and needed someone based in London to help with research and translation, both English and Swedish, acting as a bridge between herself and ghost writer Alan Burgess. First of all, she wanted me to do a sample for her to examine. She rang up very early one morning to tell me I was unable to spell. I was shocked, but drew breath when she told me that my one mistake had been to spell Rossellini with only one “l”. Otherwise, she was delighted with my work and wished to meet me. This was the beginning of many months of delightful collaboration, including much editing, as her first husband, Aron Petter Lindström, kept objecting to her descriptions of him and threatened to sue us all unless the passages were totally rewritten. This led to some controversy over my fee, as Norstedts were only prepared to pay as per my contract for text delivered, notwithstanding months of extra work I had been made to put in. It took an intervention by Ingrid before I was paid a reasonable fee for the additional work. It taught me never to take on unscheduled work without first agreeing a fee for it.

In 1979, I was approached by Norstedts. Ingrid Bergman was writing her autobiography and needed someone based in London to help with research and translation, both English and Swedish, acting as a bridge between herself and ghost writer Alan Burgess. First of all, she wanted me to do a sample for her to examine. She rang up very early one morning to tell me I was unable to spell. I was shocked, but drew breath when she told me that my one mistake had been to spell Rossellini with only one “l”. Otherwise, she was delighted with my work and wished to meet me. This was the beginning of many months of delightful collaboration, including much editing, as her first husband, Aron Petter Lindström, kept objecting to her descriptions of him and threatened to sue us all unless the passages were totally rewritten. This led to some controversy over my fee, as Norstedts were only prepared to pay as per my contract for text delivered, notwithstanding months of extra work I had been made to put in. It took an intervention by Ingrid before I was paid a reasonable fee for the additional work. It taught me never to take on unscheduled work without first agreeing a fee for it. In spite of valiant effort by the members of SELTA, working on a voluntary basis writing reviews and doing sample translations for Swedish Books, published regularly and distributed to publishers, there were still very few books being accepted for translation, so I went on working into Swedish as well. In addition to Ruth Rendell, I worked with some leading English authors, including Kazuo Ishiguro, whose crystal-clear language was a pure pleasure to work with.

In spite of valiant effort by the members of SELTA, working on a voluntary basis writing reviews and doing sample translations for Swedish Books, published regularly and distributed to publishers, there were still very few books being accepted for translation, so I went on working into Swedish as well. In addition to Ruth Rendell, I worked with some leading English authors, including Kazuo Ishiguro, whose crystal-clear language was a pure pleasure to work with. Looking at the literary market, it has gone through a complete transformation since SELTA was formed, adding one Swedish mega-bestseller to another. Just how much credit goes to the indefatigable efforts by SELTA members over the decades is of course impossible to assess, but for a founding member it is a joy to note that we have come such a long way in these 40 years. Today no self-respecting British publisher would dream of repeating the line we heard ad nauseam: that “Swedish books don’t sell.” Even so, it is fortunate that we have publishers like Norvik and Quercus prepared to take risks and publish books not only based on commercial potential but also on quality.

Looking at the literary market, it has gone through a complete transformation since SELTA was formed, adding one Swedish mega-bestseller to another. Just how much credit goes to the indefatigable efforts by SELTA members over the decades is of course impossible to assess, but for a founding member it is a joy to note that we have come such a long way in these 40 years. Today no self-respecting British publisher would dream of repeating the line we heard ad nauseam: that “Swedish books don’t sell.” Even so, it is fortunate that we have publishers like Norvik and Quercus prepared to take risks and publish books not only based on commercial potential but also on quality.

Anneli’s father was an electrician and her mother worked in a restaurant. She writes of them as ‘pappa’ and ‘mamma’, which seems simple enough, but these words are perennially problematic for translators into English in terms of register and cultural connotations. Take ‘mamma’, for example. We discussed leaving it unchanged, but does it sound a little too much like a child’s exclamation? Eventually we concluded that all solutions had their drawbacks. ‘Mama’ has too Victorian a flavour, doesn’t it? Is ‘Mum’ too British and ‘Mom’ too American? Does ‘Mummy’ sound too childish, or too upper-middle-class British? Anneli gave us some interesting background information: in Sweden there were, and perhaps still are, regional variations. In Skåne, your parents would be known as ‘mor och far’, whereas in Dalarna they would be ‘mamma och pappa’.

Anneli’s father was an electrician and her mother worked in a restaurant. She writes of them as ‘pappa’ and ‘mamma’, which seems simple enough, but these words are perennially problematic for translators into English in terms of register and cultural connotations. Take ‘mamma’, for example. We discussed leaving it unchanged, but does it sound a little too much like a child’s exclamation? Eventually we concluded that all solutions had their drawbacks. ‘Mama’ has too Victorian a flavour, doesn’t it? Is ‘Mum’ too British and ‘Mom’ too American? Does ‘Mummy’ sound too childish, or too upper-middle-class British? Anneli gave us some interesting background information: in Sweden there were, and perhaps still are, regional variations. In Skåne, your parents would be known as ‘mor och far’, whereas in Dalarna they would be ‘mamma och pappa’.

After the introductions to these two authors, we split up into two groups. I participated in the session with Susanna Alakoski. The issues we worked on dealt primarily with vocabulary (skiftflicka: doffer? shift girl?; trådrullar: bobbins? spools, reels? and the like) but also tricky citation issues such as the folk song ‘spinn min flicka spinn’ and the quote from Merrie England. What do you do when you don’t have the original text – translate it yourself? We spent a lot of time also simply enjoying the fact that we were working with a real author in real time! It became clear that both professions require a lot of research, but also that translators and authors don’t always have the same priorities or the same amount of power.

After the introductions to these two authors, we split up into two groups. I participated in the session with Susanna Alakoski. The issues we worked on dealt primarily with vocabulary (skiftflicka: doffer? shift girl?; trådrullar: bobbins? spools, reels? and the like) but also tricky citation issues such as the folk song ‘spinn min flicka spinn’ and the quote from Merrie England. What do you do when you don’t have the original text – translate it yourself? We spent a lot of time also simply enjoying the fact that we were working with a real author in real time! It became clear that both professions require a lot of research, but also that translators and authors don’t always have the same priorities or the same amount of power. I found myself in Anneli Jordahl’s session afterwards. Our first stumbling block was a brick – ‘mexitegel’. How on earth do you express all of the connotations of this word without using a run-on sentence? Another tricky single-word conundrum was ‘skönt’, the word the main character uses after telling the reader that she’s a latchkey child (latchkey was a unanimous choice for ‘nyckelbarn’). Great? Nice? We agreed there was ambiguity in this word until you got to the next sentence. Do you make things easier for the reader, or provide the same degree of vagueness? Other words we talked about were ‘skönlitteratur’, ‘niga’ (which elicited a lovely curtsey from Annie Prime!), ‘ensamförsörjande’, ‘surminen’, and the quotation from Kristina Lugn about indiscriminate reading. We also had some general discussion about translation and writing – having a real-live author there made it difficult to stick strictly to the text. But I suspect that was just fine.

I found myself in Anneli Jordahl’s session afterwards. Our first stumbling block was a brick – ‘mexitegel’. How on earth do you express all of the connotations of this word without using a run-on sentence? Another tricky single-word conundrum was ‘skönt’, the word the main character uses after telling the reader that she’s a latchkey child (latchkey was a unanimous choice for ‘nyckelbarn’). Great? Nice? We agreed there was ambiguity in this word until you got to the next sentence. Do you make things easier for the reader, or provide the same degree of vagueness? Other words we talked about were ‘skönlitteratur’, ‘niga’ (which elicited a lovely curtsey from Annie Prime!), ‘ensamförsörjande’, ‘surminen’, and the quotation from Kristina Lugn about indiscriminate reading. We also had some general discussion about translation and writing – having a real-live author there made it difficult to stick strictly to the text. But I suspect that was just fine. Much of our subsequent discussion centred on the difficulties and peculiarities that a text of this nature presents for the translator. Jonsson made the point that the translation of a graphic novel is a whole other animal; one that arguably has more in common with subtitling than with ‘classic’ literary translation, chiefly due to the paramount issue of space. Unless it is possible to increase the size of the text boxes and speech bubbles (usually the task of the letterer, a further person with whom the translator may need to interact over the course of the translation process), the translated text needs to fit in the space allocated to the original in the corresponding text box. Given that text volume tends to expand in translation from Swedish into English, this creates an obvious dilemma, similar to that faced by subtitlers.

Much of our subsequent discussion centred on the difficulties and peculiarities that a text of this nature presents for the translator. Jonsson made the point that the translation of a graphic novel is a whole other animal; one that arguably has more in common with subtitling than with ‘classic’ literary translation, chiefly due to the paramount issue of space. Unless it is possible to increase the size of the text boxes and speech bubbles (usually the task of the letterer, a further person with whom the translator may need to interact over the course of the translation process), the translated text needs to fit in the space allocated to the original in the corresponding text box. Given that text volume tends to expand in translation from Swedish into English, this creates an obvious dilemma, similar to that faced by subtitlers.

My group looked at Eija’s text; an extract from her acclaimed 2012 book Ingenbarnsland. Eija had related to us the influence of her own upbringing in the Gothenburg suburbs on her writing; coming from a Finnish migrant family, her mother a cleaner and her friends and peers with few prospects of advancement or even an average life expectancy. This background is very transparent in the text. The dialogue between the two girls in the extract is distinctively in the Gothenburg dialect, with Finnish influence and 1980s slang. This posed a challenge in terms of situating the characters in time and place for an anglophone audience. To relay the equivalent sense, we discussed how we could convey a non-standard working-class dialect without taking it to the extreme of, for example, peppering the dialogue with Geordie slang! Aside from the clear oddity of this approach, we would then be faced with the issue of whether we could make this work for a North American readership, in which case the ‘equivalent’ dialect would again have to be different.

My group looked at Eija’s text; an extract from her acclaimed 2012 book Ingenbarnsland. Eija had related to us the influence of her own upbringing in the Gothenburg suburbs on her writing; coming from a Finnish migrant family, her mother a cleaner and her friends and peers with few prospects of advancement or even an average life expectancy. This background is very transparent in the text. The dialogue between the two girls in the extract is distinctively in the Gothenburg dialect, with Finnish influence and 1980s slang. This posed a challenge in terms of situating the characters in time and place for an anglophone audience. To relay the equivalent sense, we discussed how we could convey a non-standard working-class dialect without taking it to the extreme of, for example, peppering the dialogue with Geordie slang! Aside from the clear oddity of this approach, we would then be faced with the issue of whether we could make this work for a North American readership, in which case the ‘equivalent’ dialect would again have to be different.